Trains loaded with British Mark IV Tanks stand at Plateau Station in preparation for movement to the forward area prior to the opening of the Battle of Cambrai © IWM (Q 46939). Imperial War Museums: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205215585

The 3rd Battle of Ypres was officially brought to an end on the 10th November 1917 after the capture by the Canadian Corps of Hill 52 at Passchendaele (Passendale). By that point the attention of the British military command was shifting towards a fresh operation further south. The British Third Army under General Julian Byng was gearing up for an attack on the Siegfriedstellung (the Hindenburg Line) near the city of Cambrai. The operation was to commence on the 20th November and the Tank Corps was hoping to get an opportunity to show what tanks could do in more favourable conditions than the Salient. As stated in Brigadier General Hugh Elles’s handwritten Special Order Number 6 — issued just before the battle commenced — the Tank Corps would finally now have the chance “to operate on good going in the van of the battle” [1]. Remarkably, 476 tanks had been gathered together to support the attack, 378 of them in a fighting role.

Preparations for the Cambrai attack had been underway for some weeks, but in mid-November, the battalions of the Tank Corps began to make their way towards the front line area. During the First World War, transportation was certainly not a risk-free activity. One casualty of the move to the Cambrai sector was Corporal Leonard George Hicks of “F” Battalion,Tank Corps, who died near Maricourt (Somme). Hicks came from Hackney and was a bell ringer at St Matthew’s Church, Upper Clapton, and a member of the Middlesex County Association and London Diocesan Guild of Church Bell Ringers.

Bell ringing at Upper Clapton

The Church of St Matthew dated from the 1860s, a daughter church to St John-at-Hackney [2]. The building was designed by Francis Thomas Dollman; old photographs show a large neo-gothic building with a prominent tower topped by a tall spire. The church building was severely damaged during the Second World War. While it was restored during the 1950s, the spire was removed in 1962. Sadly, the church was declared redundant in 1977 after being badly damaged by fire. A replacement church building was built on the site of the old church hall. Very little of the old church building remains now, although the stone boundary wall alongside Mount Pleasant Lane is still there.

The old church had a peal of eight bells (8, 13-2-9, in F), all cast by Mears & Stainbank (at Whitechapel) in 1868. These were removed after the fire and transferred to the Church of St Andrew and St Mary, Watton at Stone, Hertfordshire. Upper Clapton seemed to be a very active tower in the late 19th Century. According to the Felstead peals database [3], the first peal (of Grandsire Triples) was rung on 22 January 1870. Another 21 were rung before the end of the century and the records then show that peals were then rung fairly regularly until 1930. By the turn of the 20th Century, it seems that there was a highly-active band at Upper Clapton and the tower was also used for regular practices by the Ancient Society of College Youths.

We do not exactly know when Leonard learnt to ring bells. We do know from the Ringing World, however, that he rang the tenor bell for a quarter peal (1260 changes) of Stedman Caters at St Mary’s Church, Walthamstow on 2 November 1914 [4].

Mark IV tank Ashford (Kent), now a war memorial

Leonard George Hicks

Leonard George Hicks was born in the 2nd quarter of 1892 at Clapton. His parents were Alfred John and Alice Hicks. The 1901 Census describes Alfred as a builder’s foreman, but by 1911 he was a builder, working on his own account. Leonard first features in the 1901 Census, aged 9 and living with his parents and seven siblings at 30 Saratoga Road, Clapton. By 1911, they had moved to 11 Comberton Road, Upper Clapton. Leonard was by then 18 years old and working as a ship broker’s clerk.

In the 1st quarter of 1917, Leonard married Lorna Edith Leopold in the Hackney registration district. Lorna had been born at Clapton in the 3rd quarter of 1892. Her parents were Edward and Mary Leopold. Edward Leopold had been born in the Netherlands and in 1901 was working as a banker’s clerk. By 1911, Lorna was eighteen years old and working as an apprentice in wholesale drapery.

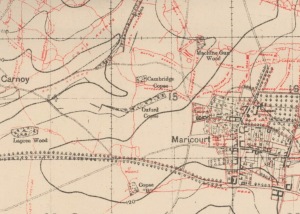

Maricourt (Somme). Detail from Trench Map 62C.NW; Scale: 1:20000; Edition: 4B; Published: March 1918; Trenches corrected to 6 March 1918; http://maps.nls.uk/view/101465278 Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I have not been able to find out that much about Leonard Hicks’s service career. Soldiers Died in the Great War states that he had served in the Norfolk Regiment (Service No. 12591) before joining the Tank Corps. At the time of his death on the 14 November 1917, he was serving with “F” Battalion of the Tank Corps, who were by then in the process of preparing for the Battle of Cambrai. “F” Battalion formed part of the 3rd Tank Brigade at Cambrai, fighting on the right flank of the attack supporting the British 36th Infantry Brigade (part of 12th (Eastern) Division). Looking at the battalion war diary [5], it seems that Hicks was killed in rail accident on his way to take part in the attack.

British Mark IV Female Tanks being loaded aboard flat-bed railway trucks at Plateau Station in preparation for transportation to the forward area prior to the opening of the Battle of Cambrai © IWM (Q 46930). Imperial War Museums: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/ object/205215579

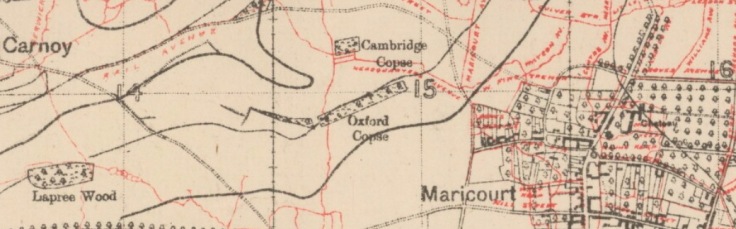

On the 14 and 15 November 1917, “F” Battalion of the Tank Corps passed through Maricourt en route to Cambrai, as entrained tanks bound for the battle were reorganised at the railhead at nearby Plateau Station. Something went wrong with the train carrying Corporal Hicks’s company. The battalion war diary for the 15 November records the following:

All trains arrived at PLATEAU STATION.

18 Coy’s train nearly came to grief owing to one of the trucks, conveying personnel, jumping the points at a crossing not far from the station and becoming derailed, thus killing two crew and injuring 8 others. A certain amount of equipment was also lost owing to this accident and the train delayed.

The two “F” Battalion men killed would appear to be Corporal Hicks and Gunner Lewis Hall. The CWGC database records that both died on the 14 November and both are buried in Peronne Road Cemetery in Maricourt. The information about Peronne Road Cemetery and other records available from the CWGC suggest that Hicks and Hall were two of the 38 men concentrated there after the war from La Côte Military Cemetery, which I think was a little further west along the current D938 road linking Albert and Peronne (for his original place of burial, Hicks’s CWGC records reference the Trench Map reference: 62c.A.15.c.5.0).

Railways near Maricourt. Detail from Trench Map 62D.NE; Scale: 1:20000; Edition: 3B; Published: August 1918; Trenches corrected to 3 August 1918. http://maps.nls.uk/view/101465314 Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Leonard George Hicks’s death was reported in the Ringing World of the 7 December 1917 [6]:

CLAPTON’S THIRD LOSS.

On Saturday last, in the ringing room of St Matthew’s, Clapton ringers from various parishes of London assembled to show respect to a late member of the St. Matthew’s Society, Leonard G. Hicks (aged 26 years), who gave his life in France on November 14th. – After a short appreciation and prayer by the Vicar (the Rev. O. R. Dawson) the bells were rung half-muffled for the whole-pull and stand and in several touches, those taking part being: Miss Grace Adams, Messrs. H. C. Alford, O. L. Twist, W. T. Powell, J. Barrv, A. S Pettett, J. Hunt, H. F. Hull, H. T. Scarlett and S. S. Dunwell. A 630 of Grandsire Triples was rung by: H. T. Scarlett 1, H. C. Alford 2, Jos. Barry 3, W. T. Powell 4, Jas. Hunt (conductor) 5, O. L. Twist 6, H. F. Hull 7, A. S. Pettett 8.

St. Matthew’s has now lost three of its ringing members, out of eight serving with the colours in this war, the late esteemed Master, Capt. H. J. Sudell having died of wounds received in the Dardanelles on August 27th 1915, and the equally respected treasurer, Pte. G. H. Orford, from wounds received in France, June 24th, 1916.

Early the following year, Leonard Hicks’s death was also announced at a meeting of his district bellringing society, the North and East District of the Middlesex County Association [7]. Other district deaths announced at that meeting were those of Lieutenant C. J. W. Alderton (St James’, Clerkenwell), and Mr W. Childs (Barnet).

Incidentally, Second Lieutenant Charles John Woodward Alderton was also a casualty of the Battle of Cambrai. He served with the 1/7th Gordon Highlanders in 153rd Infantry Brigade, part of 51st (Highland) Division. Alderton died on the 20 November 1917 – the opening day of the battle – while attached to the 1/5th Gordons. He is buried in Metz-en-Couture Communal Cemetery Extension, although his battlefield cross is now in St Martin’s Church, Epsom. His name is also listed on the war memorial in St James’ Church, Clerkenwell [8].

Tank Corps badge, Church of St Mary Aldermary (City of London)

“F” Battalion, Tank Corps

It is not clear how long Corporal Hicks had been serving with the Tank Corps. All we know is that when he died he was serving with the 18th Tank Company, which together with the 16th and 17th Companies made up “F” Battalion (from 1918, the 6th Battalion). According to its war diary [5], the battalion had left Bovington Camp (Dorset) in May 1917, travelling to France via Southampton and Le Havre. The battalion were at first based at Auchy-lès-Hesdin (Pas-de-Calais), although time was also spent training at Wailly.

In July 1917, “F” Battalion moved to the Ypres Salient, where the Tank Corps headquarters were based at La Lovie Camp and the tanks around Oosthoek Wood, near Elverdinghe [9]. The 16th and 17th Companies moved up to the front and took part in the first action of the 3rd Battle of Ypres (the Battle of Pilckem Ridge) on the 31 July, fighting in the area north east of Ypres near St Jean and Oxford Road. On the 22 August, the 18th Company took part in an action near St Julien (Gallipoli Farm), where one of the Company’s tanks — Mark IV F41 “Fray Bentos,” commanded by 2nd Lt. G. Hill — famously remained in action for several days ditched in no mans’ land, until finally abandoned on the night of the 24th. The Salient did not provide particularly suitable ground for tanks, and the bad weather made things much worse. On the 27 August, the battalion war diary recorded: “Arrangements had previously been made for the tanks to cooperate with the 61st Divn. in an attack on this date but, owing to the state of the weather, the attack was not carried out by the tanks as the ground was impassable even for the infantry” [5]. For tanks, the 3rd Battle of Ypres became infamous for the extent of its “tank graveyards,” especially in the areas around the Menin Road (Hooge), Frezenberg, St Julien, and Poelcapelle [10].

In mid-September, “F” Battalion moved from La Lovie to Blairville Camp, where they spent over a month in further training, e.g. exploring how tanks could tackle substantial obstacles like railway embankments. In late October, the battalion moved back to Auchy, and underwent even more training. Then, on the 11 November, the battalion war diary indicated that a new operation was in the offing [5]:

Preliminary instructions were received of an intended attack to take place shortly in which this battalion will operate with the 12th Division, and will probably move to the Forward Area on the 14th inst.

As expected, the main move commenced on the 14th November [5]:

16 and 17 Coys moved off to Central Workshops, as also the six spare tanks. All tanks were entrained without difficulty except for two tanks of 17 Coy which broke down, necessitating two new tanks being drawn to replace them, and also a broken track which delayed 16 Coy’s entrainment.

All trains arrived at PLATEAU STATION.

Without Corporal Hicks and Gunner Hall, “F” Battalion would go on to take part in the opening phase of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917, with the 18th Company supporting 36th Infantry Brigade (part of 12th Division) in the area around La Vacquerie and Bonavis Farm. The 12th Division reached its objectives by midday, and then began to deploy its brigades to protect the southern flank of III Corps. In this sector — as in others — many tanks were either knocked out or ditched, but sufficient remained to move forward in the afternoon to the St Quentin Canal. While trying to cross the canal, a male “F” Battalion tank, F22 “Flying Fox II,” managed to demolish the canal bridge at Masnières [11].

The Battle of Cambrai would eventually lead to disappointment and recrimination. The Germans counter-attacked on the 30 November and by the 7 December had reclaimed much of the ground that had been captured with much fanfare on the 20th November and the days following.

Update, November 14, 2017:

Following the first publication of this blog, David Underdown put me in touch on Twitter with Stephen Pope, the author of: The first tank crews: the lives of the tankmen who fought at the Battle of Flers Courcelette, 15 September 1916 (Helion, 2016). He was able to add that Hicks’s medal index card shows that he served with the 7th Battalion, Norfolk Regiment in France from 30 May 1915, and that his Tank Corps service number indicates that he joined the tanks in early 1917. My sincere thanks to them both.

References:

[1] Brigadier-General Hugh Elles, Special Order No 6, 19 November 1917: http://www.greenflash.org.uk/cambrai/06.html

[2] The Story of St Matthew’s Church, Upper Clapton: https://stmatthewse5.wordpress.com/home/about/the-story-of-st-matthews/

[3] Felstead peals database: https://cccbr.org.uk/felstead/tbid.php?tid=7031

[4] Ringing World, 23 January 1914, p. 65.

[5] WO 95/107/3, 6th Battalion, Tank Corps: 6 Battalion, Tank Corps War Diary, May 1917 – March 1919, The National Archives, Kew.

[6] Ringing World, 7 December 1917, p. 389.

[7] Ringing World, 8 February 1918, p. 43.

[8] Epsom and Elwell War Memorials: http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/WarMemorialsSurnamesA.html

[9] Robert Baccarne, Poelcapelle 1917: a trail of wrecked tanks; English language version of: Poelcapelle 1917: een spoor van tankwrakken (Langemark-Poelkapelle: Robert Baccarne, 2007).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Jack Horsfall and Nigel Cave, Cambrai: the right hook (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1999), p. 48.

[…] 1917. Six infantry divisions of the British Third Army, supported by nine battalions of the Tank Corps, attacked Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) defences to the west and south-west of the city of […]

By: “Hysterical, and un-English” — joy bells for Cambrai | Opusculum on November 20, 2017

at 8:13 am

[…] 1917, when six Infantry Divisions of the British Third Army, supported by nine battalions of the Tank Corps, attacked Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) defences to the west and south-west of the city of […]

By: Rifleman Alfred Pocock, 12th Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles | Opusculum on November 22, 2017

at 9:14 am