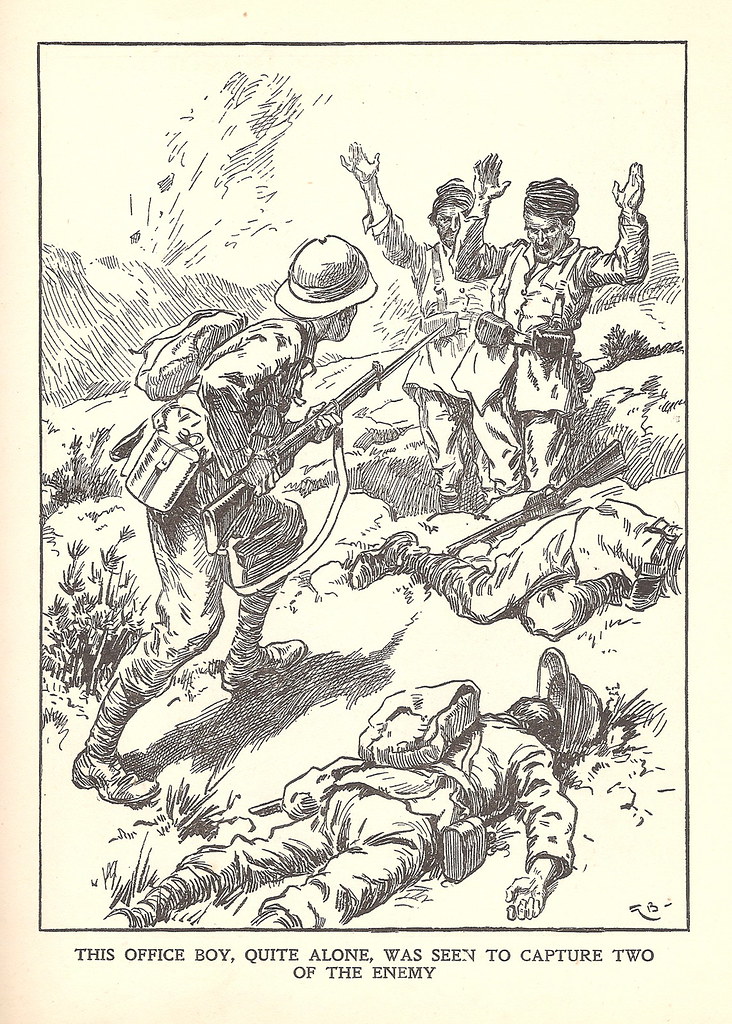

“This office boy, quite alone, was seen to capture two of the enemy;” illustration by Gordon Browne. Source: John Lea, Brave boys and girls in wartime (Blackie, ca. 1918)

9612 Private Cyril Edward Cook of the 5th (Service) Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment was killed in action at Gallipoli on the 15th December 1915, aged seventeen. Cyril was the son of Arthur Ernest and Florence Ethel Cook of East Finchley. He was just one of many teenage solders that died during the First World War, but there seems to have been something in his story that attracted the attention of the media at the time, so it found its way into newspapers all over the world and finally into a children’s book. These stories can now be traced, at least in part, via the products of newspaper digitisation initiatives.

Private Cook’s death was first reported in his local newspaper, the Hendon & Finchley Times, on the 21st January 1916. While misspelling his family name, it was a fairly standard obituary for the time, even if was a little longer than most. It incorporated information and quotations from correspondence that could only have been provided by the family, including the contents of a letter from a comrade of Cyril’s, Private Charles Van Humbeck [1]:

PTE. CYRIL COOKE.

Mr. and Mrs. Cooke, of No. 2, Long-lane, East Finchley, have received official notification of the death of their son, Pte. Cyril E. Cooke, who was serving in the 5th Wilts regiment. It is stated that he was killed in action on December 15th at the Dardanelles.

The dead soldier was only fifteen when he joined the Army just after the commencement of the war, and went with his regiment to the Dardanelles last July. In a letter received by Mrs. Cooke, a comrade of her son’s, Pte. Chas. Van Humbeck, says that Cooke was brave to the point of recklessness, and with graphic detail proceeds to give an account of a retreat in which Cooke was killed. The same writer tells how Cooke captured at the point of the bayonet two Turks single-handed on each of two occasions.

The hero was a one-time scholar of Long-lane Council School, and attended Holy Trinity Sunday School. Before his enlistment he was a clerk in the correspondence department of a West End firm.

9607 Private Charles Van Humbeck also came from London. His letter to the family was also quoted in a far more sensationalised account of Private Cook’s service which was published in The Dundee People’s Journal of the 29th January 1916 [2]:

CAPTURED 4 TURKS.

BOY DOES HIS BIT BEFORE HE DIES.

“I nearly died of laughing when I saw the boy holding up the big Turks at the point of the bayonet” says Private Charles von Humbeck, in a letter to Mrs Cooke, the mother of Private Cyril E. Cooke, a boy of 16 years, who was killed in Gallipoli.

Cooke enlisted at the age of fifteen in the 5th Wiltshire Regiment, just after the outbreak of war, and a few weeks ago wrote to a friend in London, “We are making the best of a bad job, but with a stiff upper lip,” and now news has been received by his parents at East Finchley that he was killed on December 15th.

Eighteen months ago Cyril Cooke was an office boy. A roguish-faced lad, with laughing eyes and an attractive manner, he was a great favourite with the staff, and one day in August 1914 he astonished the manager of his department by telling him that he had enlisted. After ten months training he went to the Dardanelles with his regiment.

His comrade, writing home, told his parents how young Cooke twice captured two Turks at the point of the bayonet. In one of his own letters Cyril said – “I shall be glad when it is all over, but until then I am going to do my bit, and do it thoroughly.”

From that, the story would find its way into newspapers published in several different countries. In Australia, for example, a reworked version was published in the Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser of the 7th April 1916 [3]:

Boy’s Four Turks.

“We are making the best of a bad job, but with a stiff upper lip,” wrote Private Cyril E. Cooke, 5th Wiltshire Regiment, to a friend in London. Cooke enlisted at the age of 15, just after the outbreak of the war, and news has now been received by his parents at East Finchley that the boy was killed on December 15 in Gallipoli, whore he had been for several months. In a letter to Mrs. Cooke Private Charles Van Humbeck, of her son’s regiment, tells how young Cooke twice captured two Turks at the point of the bayonet. ”I nearly died of laughing,” he writes, “when I saw the boy holding up the big Turks at the point of the bayonet.” Eighteen months ago Cyril Cooke was an office boy. A roguish-faced boy with laughing, eyes and an attractive manner, he was a great favorite [with the] staff. One day in August, 1914, he astonished the manager of his department by telling him that he had enlisted. After 10 months training he went to the Dardanelles with his regiment.

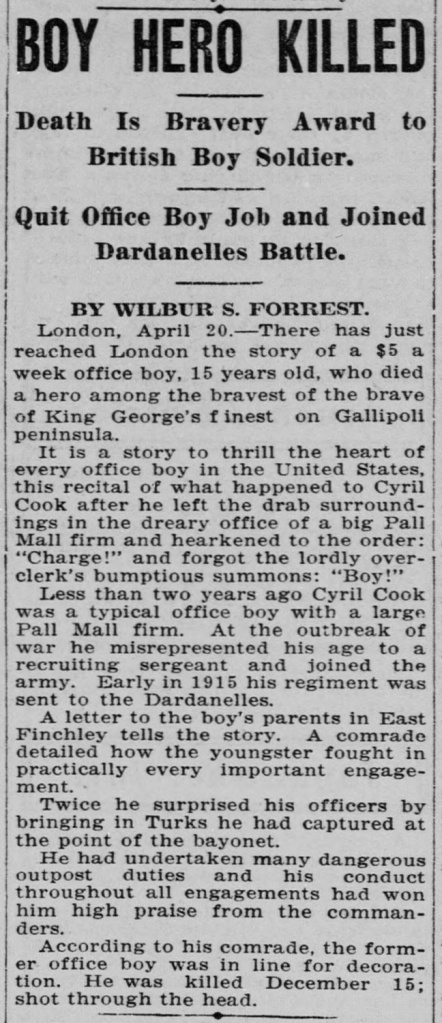

The death of Private Cook was also covered by several newspapers in the United States. The examples that I’ve found (via the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America) all used the same stock text, written by Wilbur S. Forrest of the United Press (in 1927, as a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, Forrest would also send out the first report on Charles A. Lindbergh’s landing in Paris) [4]:

Topeka State Journal, 22 April 1916, p. 13. Source: Kansas State Historical Society, via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress.

The tone of Forrest’s article is light-hearted, even jocular. That it ends with the death of a teenager, “shot through the head,” might seem more than slightly disturbing in the present day. It also adds a few fresh details, although their provenance is not given. The following version appeared in the Alaskan newspaper, The Seward Gateway on the 22nd April 1916 [5]:

OFFICE BOY WHO WAS GENUINE HERO IN BATTLE

By WILBUR S. FORREST

Special to Gateway by United Press.

London, April 19. – There has just reached London the story of a $5 a week office boy, 15 years old, who died a hero among the bravest of the brave of King George’s finest on Gallipoli peninsula.

It is a story to thrill the heart of every office boy in the United States, this recital of what happened to Cyril Cook after he left the drab surroundings of a big Pall Mall firm and hearkened to the order: “Charge!” and forgot the lordly overclerk’s bumptious summons: “Boy!”

Less than two years ago Cyril Cook was a typical office boy with a large Pall Mall firm. At the outbreak of war he misrepresented his age to a recruiting sergeant and joined the army. Early in 1915 his regiment was sent to the Dardanelles.

A letter to the boy’s parents in East Finchley tells the story. A comrade detailed how the youngster fought in practically every important engagement.

Twice he surprised his officers by bringing in Turks he had captured at the point of the bayonet.

He had undertaken many dangerous outpost duties and his conduct throughout all engagements had won him high praise from the commanders.

According to his comrade, the former office boy was in line for a decoration. He was killed December 15th; shot through the head.

Towards the end of the war, Private Cook’s story would also be told in a children’s book, Brave Boys and Girls in Wartime, written by John Lea, with illustrations by H. M. Brock and Gordon Browne (Blackie, 1918).

John Lea was the pen name of John Lea Bricknell (1868-1952), who wrote many books for children [6]. Brave Boys and Girls is a collection of twenty-eight illustrated “true stories” of children’s bravery in war, including stories of a French peasant girl that brought jugs of coffee to British soldiers in the trenches during the winter of 1915, a girl that burnt her hands beating out the flames of a fire that had engulfed her sister during a Zeppelin raid on Southend, as well as tales of Boy Scouts and Girl Guides making themselves useful. Several of the stories relate to boys on active service.

John Lea, Brave boys and girls in wartime (Blackie, 1918)

The item on Private Cook turns part of the story into an invented dialogue, but it represents, in essence, a fairly straightforward reworking of the information provided by the People’s Journal article, with its moral lessons drawn out for a younger audience [7]:

An Office Boy who fought for his King

ONE August day in 1914 the manager of part of a large London business house was sitting in his office, when someone knocked on the door in a manner that seemed to say: please let me in at once!”

The permission was given, and the office boy entered – Cyril E. Cooke, aged fifteen.

“Please sir,” said he in breathless tones, “I have enlisted in the army, and shall soon be leaving you to enter the ranks.”

“Impossible!” cried the astonished manager. “Why, you are only fifteen, and a mere boy.”

But it was quite true; and before many days had passed Cyril Cooke was training for soldier’s work. Ten months later he was at the Dardanelles, fighting the Turks, and brave letters came home to his mother to say: “We are making the best of a bad job with a stiff upper lip.” Most boys and girls will know what this means: We are keeping up our courage in spite of many troubles. But those who saw Cyril Cooke doing his duty were able to tell tales about his bravery which he was too modest to tell himself. On two occasions this young office boy, quite alone, was seen to advance with fixed bayonet and capture two of the enemy, bringing them in as prisoners.

Alas! the promising young soldier, to the great regret of his comrades, was killed on the 15th December 1915, after writing home the gallant message: “I shall be glad when it is all over, but until then I am going to do my bit, and do it thoroughly.” He kept his word.

The item was accompanied by an illustration by Gordon Browne, purporting to illustrate Private Cook’s capture of two Turkish soldiers [8]. Browne (1858-1932) was a prolific illustrator of children’s books, including those of G. A. Henty and Percy F. Westerman.

The accounts are remarkable in that there seems to be no sorrow for the loss of such a young soldier, nor is there a hint of censure for the British Army accepting such an obviously under-age recruit. The tone throughout remains that of a boy “sticking it out” and “doing his bit thoroughly,” regardless of consequences.

It is also interesting that there are some aspects of the story that always remain obscure. For example, readers are never given the identity of the company that Cook left in order to enlist — although Forrest confidently assures his audience that it was a dreary Pall Mall firm, with a quota of ‘bumptious’ overclerks. There is also next-to-no interest in Private Cook’s background and family, except for that single fact that he had worked as an office boy and came from East Finchley. The later accounts also barely show any interest in the unit in which Private Cook had served, with the result that the stories seem a bit detached from the realities of what the 5th Wiltshires might have endured at Anzac and Suvla.

Cyril Edward Cook:

Moving beyond the newspaper articles, it has been possible to discover some additional details about Private Cook’s life and family background from the genealogical and census records made available by the Findmypast service [9].

Cyril Edward Cook was born at Barking, then in Essex, on the 31st August 1898, the son of Arthur Ernest Cook and Florence Ethel Cook (née Goodchild). He was baptised at St Margaret’s, Barking on the 18th September the same year, when the family were resident at 59 Axe Street, Barking [10].

The family had moved to Finchley by the time of the 1901 Census. It records them living at 5, Park Hall Parade, Finchley, part of the household of James S. Newman, a butcher. As well as the five members of the Newman family, the household included four servants, three of them being journeymen butchers. Aged twenty-eight, Arthur E. Cook was one of those journeymen butchers. living with his wife (who was aged 29) and three children: Ernest A. (aged 4), Cyril E. (3), and Albert V. (7 months).

At the time of the 1911 Census, the family were living at Ivy Lodge, Long Lane East, East Finchley. Cyril was twelve years old and still at school. He was the second eldest of five children, the others being: Ernest Arthur (aged 14), Albert Victor (10), Louis Charles Sydney (8), and Florence Ethel Grace (5). Arthur Ernest Cook was thirty-eight years old and working as a butcher’s manager, while Florence Ethel Cook was thirty-nine.

Florence Ethel Goodchild had been born at Baldock (Hertfordshire) in the first quarter of 1871, the daughter of James and Elizabeth Grace Goodchild, and was baptised there on the 11th May 1873. Arthur Ernest Cook was born at Bethnal Green in the second quarter of 1872, the son of William Cook and Emma Mary Cook (née Connew). They married at St Albans (registration district) in the second quarter of 1896. By the time of the 1911 Census, they had been married fifteen years and had five children, of whom Cyril was their second eldest.

The Soldiers Died in the Great War database states that Cyril Edward Cook enlisted at Lambeth. If, as the newspaper obituaries suggest, he joined up immediately after the outbreak of war, he would definitely still have (just) been fifteen years old.

Private Cook has no-known family link with the county of Wiltshire. How he (and Private Van Humbeck) ended up in the 5th Wiltshires remains obscure, but a clue may be found in some notes made by 11687 Private S. B. Ayling, which have been published in Paula Perry’s history of the battalion [11]. Ayling was one of several persons working in the London City Office of the Cunard Line who were trying to enlist at the end of August 1914. They found that several of the recruiting offices for London Regiment battalions were already full up, but a group of them eventually managed to enlist at a marquee on Horse Guards Parade, receiving their King’s Shilling and instructions to travel by train to Devizes.

Private Cook’s death is mentioned briefly in the battalion War Diary [12]:

15 & 16/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

The Battalion relieved by 4/SWB [4th South Wales Borderers] and proceeded to reserve lines. Pte Cook killed while on Bde. Fatigue.

Battalion War Diaries did not routinely name non-officer casualties, but it seems that the adjutants of the 5th Wiltshires did not always adhere to that convention during the Gallipoli campaign.

The 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment at Gallipoli:

The 5th (Service) Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment was formed at Assaye Barracks, Tidworth in August 1914 as a New Army unit. It trained first at Cirencester and then at Cowshot, near Woking. On the 1st July 1915, the battalion sailed from Avonmouth for the Mediterranean on the SS Franconia. The battalion had become part of 40th Infantry Brigade in the 13th (Western) Division, one of four divisions sent to the Dardanelles to strengthen the campaign there. The 13th were one of three New Army Divisions sent to Gallipoli, the others being the 10th (Irish) and 11th (Northern) Divisions.

Helles:

The Franconia’s first port of call in the Mediterranean was Malta, but the battalion sailed on to Alexandria and then to Mudros Bay (Lemnos), arriving there on the 15th July. On the following day, the first of two contingents of the 5th Wiltshires sailed for the Gallipoli peninsula, landing at V Beach at Cape Helles after midnight on the 17th and marching to Gully Beach. During the original landings at Gallipoli, the 29th Division had landed at various places at Helles on the 25th April, but progress had been slow and the opportunity to advance up the peninsula and to link up with the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) landings further north had been lost. After their arrival at Helles, the 5th Wiltshires spent 10 days in fire trenches at before being relieved on the 29th July by fusilier units of the 86th Infantry Brigade on the 29th July and returning to Mudros.

Anzac and Chunuk Bair:

By the end of July, preparations for a new offensive at Gallipoli were well in hand. The August Offensive was to have two main components. Firstly, there would be an attempt to break out of the pocket established at Anzac and capture the high ground of the Sari Bair ridge. This would be shielded by the landing of fresh troops from IX Corps at Suvla Bay, who would go on to capture the higher ground to the east and link-up with the breakout from Anzac. The landings at Suvla, which commenced on the evening of the 6th August, would be spearheaded by the 11th (Northern) Division. While part of IX Corps, the 13th Division would instead be directed to the Anzac sector, where they would support the attempted breakout there. While there would be diversionary attacks (mainly Australian) at Lone Pine, The Nek, Dead Man’s Ridge, and Turkish Quinn’s, the main attempt to capture the Sari Bair ridge would be led by the commander of the New Zealand and Australian Division, Major-General Alexander Godley. For this the Division was to be reinforced by the 29th (Indian) Brigade and the New Army battalions of the 13th Division.

The 5th Wiltshires, therefore, landed at Anzac Cove on the night of the 4th August 1915 and moved to White Valley. Landings were conducted at night in an attempt to conceal the build-up to the planned offensive from the Turks.

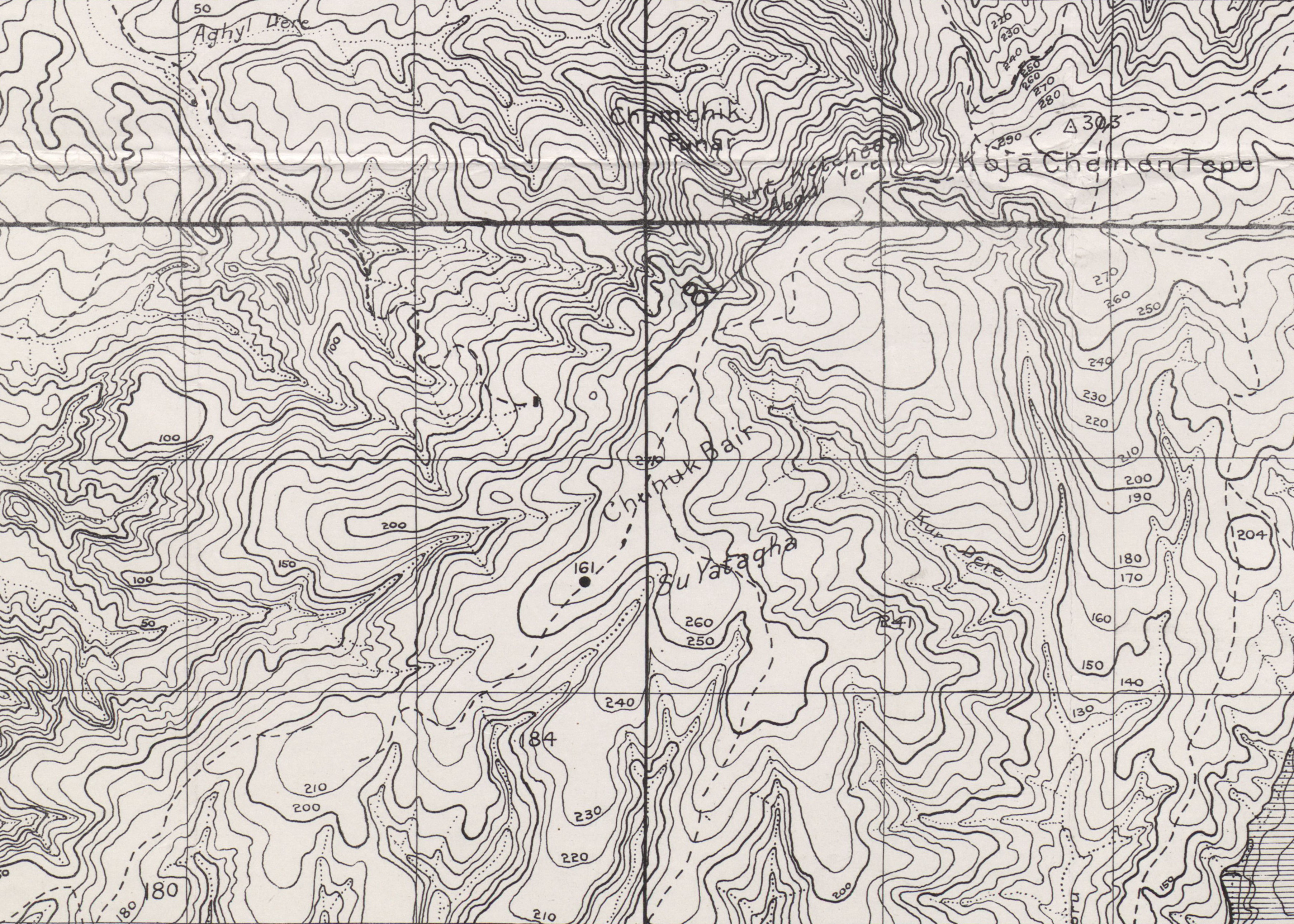

On the 6th August, the 5th Wiltshires and the 4th South Wales Borderers moved north as part of the “Left Covering Force” commanded by Brigadier-General J. H. du B. Travers (40 Brigade). The battalions moved north parallel to the coast, crossed the mouth of a valley called Aghyl Dere and occupied Damajelik Bair, taking a number of Turkish prisoners in the process. In the meantime, the New Zealand and Australian Division, supported by the 29th (Indian) Brigade, had managed to gain a tenuous hold near the summit plateau of Chunuk Bair.

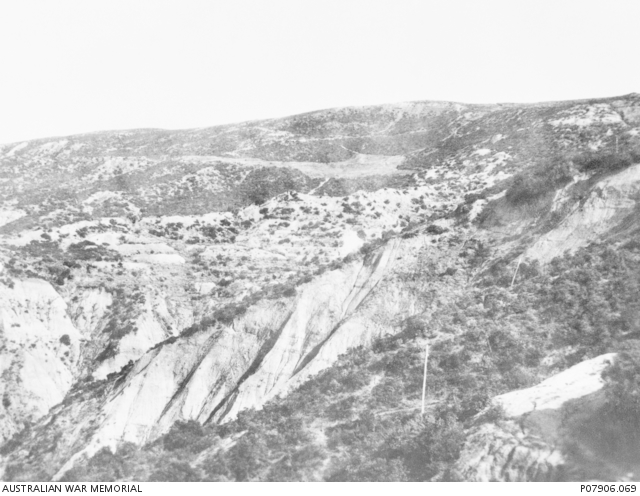

On the 8th August, the 5th Wiltshires joined a composite brigade commanded by Brigadier-General Anthony Hugh Baldwin (38th Brigade), who had been ordered to spearhead another attempt to assault the Sari Bair ridge by capturing Hill Q, on the ridge-line north of Chunuk Bair. Baldwin’s brigade started moving up the Chailak Dere on the 8th August but their initial progress was slow. Then, rather than taking the already-well-established route to Chunuk Bair via The Apex, which had been used by the New Zealanders, the brigade diverted onto an unexplored route that led them into the Aghyl Dere, which led to additional delays. By the early morning of the 9th, the force was arriving just short of an enclosure known as The Farm. By the time that Baldwin’s brigade had arrived there, the linked flanking attacks on the Sari Bair ridge had already gone in and had been repulsed by the Turks. Without the flanking attacks, the main attempt to capture Hill Q also failed. Charles Bean, the Australian Official Historian, clearly regarded this attack as an opportunity lost [13]:

Thus in Godley’s third attempt upon Sari Bair the right (or New Zealand) “column” was throughout engaged in desperately resisting attack; the left (Gurkha and British) “column” reached the crest near “Q” with the enemy in full retreat, but was driven off by the shells of its own artillery; and Baldwin’s central column, which, if it had been on the crest when the bombardment ended, might have restored the position, had been diverted into the Aghyl Dere, through whose depths at the crucial moment it was still toiling.

The 6th Loyal North Lancashire Regiment (38th Brigade) had already moved up to The Apex to act as reserve to the New Zealand Brigade on Chunuk Bair. Needing a second battalion to take over positions on Chunuk Bair from the New Zealanders, Major-General F. C. Shaw (commanding 13th Division) chose the 5th Wiltshires. The battalion, less D Company and part of B Company, which seems to have remained in the area around The Farm, moved up towards Chunuk Bair on the night of the 9th/10th August, but arrived late. In the meantime, the New Zealand units in the front line had been withdrawn, leaving the positions on Chunuk Bair and The Pinnacle in the hands of the Loyals. Bean provides an account of the arrival of the 5th Wiltshires [14]:

Eventually, at about 2 o’clock two-and-a-half companies of the battalion reached The Apex, and were thence guided by a New Zealander to the position on Chunuk Bair. Here Colonel Carden met Colonel Levinge of the North Lancashire. As all the trenches on Chunuk Bair were shallow, and the rearmost full of wounded, it was decided that the 5th Wiltshire should not occupy them, but should remain lower down in the spoon-shaped hollow at the head of the Sazli, near the point where the wounded were mainly collected. Here, having been told by the guide that they were in shelter, the Wiltshire waited; but at dawn they found themselves under a sniping fire, and consequently took off their equipment and began to entrench.

The War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires quotes an officer describing their position as a “cup-shaped deformation at the head of the Gulley to the right and some distance in front of our salient” [15]. Stephen Chambers identifies this as a location at the head of the Sazli Beit Dere [16].

Detail from map of Koja Chemen Tepe. Mediterranean Expeditionary Force GHQ, ca. 1915. Source: A collection of military maps of the Gallipoli Peninsula, G.H.Q. M.E.F, 1915; British Library, Digital Store Maps 43336.(21.), No. 40; Crown Copyright, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

It was not long before everything changed. Under the guidance of Mustafa Kemal, the Turks had been preparing a massive counter-attack. At 4.30 am on the 10th August, they attacked in force, pushing the Loyals and Wiltshires off Chunuk Bair. A note in the battalion War Diary states that the Wiltshires were “overwhelmed in their bivouac before they could ‘stand to’ (no alarm had been given), but the division of Turks brought over from Asia who advanced down the slope in mass” [17]. The situation was eventually stabilised with the help of the New Zealand machine-gunners and naval artillery, but the counter-attack marked the end of Allied attempts to hold on to Chunuk Bair.

Many of the Wiltshires that had not been killed in the initial onslaught were pushed into the Sazli Beit Dere, from which there was no easy escape in daylight. Some were able to escape after dark. Chambers quotes Lieutenant Walter Evans of the 8th Welsh Regiment (13th Division pioneers) [18]:

They [the survivors] were obliged to abandon all their wounded and that is why there are so many missing. The wounded in the gully remained there all day, many dying, and in the evening, when it was dark, all who were able ran back over the hill to where our bivouac was on Saturday night.

Other survivors were effectively trapped in the zone between the lines, where some would remain for weeks. Peter Liddle comments on the situation of some of these [19]:

Perhaps the most pitiful fate was that of survivors of the 5th Wiltshires, who lay between the lines for a fortnight in the Sazli Beit Dere. Water was found from a spring but was apparently supplemented by some by sympathetic Turks who knew where they were but neither fired on them nor took them prisoner. In an attempt to escape, some were killed by the Australian who mistook them for the enemy, and others by the Turks, who had observed their dash. Two men managed to reach the New Zealanders and one, in his weakened position, was carried out to help to locate and rescue the five remaining survivors.

The battalion War Diary contains some later annotations by Lieutenant H. B. L. Braund, one of which seems to corroborate the latter story: “a party of 5 men was rescued from the Gulley having been there 16 days – i.e., from Aug 10 – Aug 26th” [20].

A view of The Farm and Chunuk Bair from Table Top; one of a series of photographs taken on Gallipoli by the Australian War Records Section, 1919. Source: Australian War Memorial P07906.069 (Public Domain): https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1229063

Those in D Company and part of B also got caught up in the same Turkish counter-attack. The War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires states that D Company relieved the Gurkhas with the (6th) Royal Irish Rifles in reserve: “position attacked at dawn on Tuesday (10th) morning and through the retirement of regiments on right and left, D company are left ‘in the air’” [p10]. The battalion retreated into a gully, from where they counter-attacked with great loss. They eventually retired from the gully in the evening. Bean summarised the situation as follows [21]:

South of The Farm, until about 9 o’clock, eighty of the 10th Hampshire and 5th Wiltshire held to the slope below the Pinnacle, and at The Farm itself the Royal Irish Rifles were still clinging to the hillside at 10.30.

General Baldwin himself was killed during the fighting on the 10th, and the vacated Farm position was occupied by the Turks over subsequent days.

The casualties suffered by the 5th Wiltshires on the 10th August were horrendous. The roll of honour appended to the published battalion War Diary lists the names of 144 dead for that date alone, and there were many more that must have died during the wider operations at Anzac. The dead included the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel John Carden, CMG, a veteran of the Matabele Wars and the South African War. The War Diary itself lists twelve officer casualties (killed, missing, or wounded) and notes that the battalion afterwards only mustered around 420 on the beach, 76 of whom had lately arrived from Lemnos [22].

IWM HU 119589: Lieutenant Colonel John Carden; Copyright: © Imperial War Museums; Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205291825

It is not entirely clear where Private Cook might have been during these actions. His newspaper obituaries do not mention them at all, and it is difficult to speculate without some additional information, e.g. knowing which Company he was serving in. The name of Cook’s friend Private Van Humbeck was initially published as being missing, but this was later corrected to state that he had re-joined his unit [23]. It is possible that Van Humbeck was one of those trapped in no man’s land after the Turkish counter-attack of the 10th August, but it seems unlikely that we will ever know for sure.

Suvla:

The 5th Wiltshires reformed on the beach at Anzac and on the 15th August moved up once again to the area just below The Apex, where they spent a few days digging trenches on Rhododendron Hill. On the 5th September, the battalion and the 8th Welsh Regiment moved to Lala Baba, in the Suvla sector, re-joining IX Corps. The 5th Wiltshires would remain there until the evacuation from Suvla and Anzac in mid-December. There would be no more offensives, but over the next few months the men would have to endure Turkish shelling and sniping, sickness (including much dysentery), and bad-weather. At the end of November, there were storms and flooding, followed by snow, blizzards, and bitterly-cold temperatures. In those conditions, the fighting sometimes got ignored in favour of simple survival.

The decision to evacuate Suvla and Anzac was taken in early December, although planning for the eventuality had already been underway for some weeks. The War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires mentioned the evacuation of stores on the 9th and 10th December, so Private Cook was killed while the battalion’s preparations for leaving Suvla were well underway. His death was mentioned briefly in the War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires, which was otherwise full of information about the evacuation [24]:

12 & 13/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

Fire trenches. Evacuation of stores continued. Party sent in advance of men with bad feet. Turks shell CHOCOLATE HILL at night.14/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

Fire trenches. 2/Lt O’Brien and party of 6 men attached to Bde H.Q. for duty as guides etc. during evacuations. Lt Brown proceeded with Div. Advance party. Inspection by Brigadier General of Bn. in full marching order.

Patrol. 2/Lt Webb and 2 grenadiers went out and approached within 30 yards of Turkish Trenches on which they threw 3 bombs and retired under fire.

Remarks: Patrol.15 & 16/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

The Battalion relieved by 4/SWB [4th South Wales Borderers] and proceeded to reserve lines. Pte Cook killed while on Bde. Fatigue.”

From the casualty lists attached to the published version of the battalion War Diary [25], Private Cook seems to have been the 5th Wiltshires’ final combat casualty at Suvla; he was, at least, the final member of the battalion to be killed in action during 1915 (others would die from other causes, and Pte. Albert Edward Brown would be killed in action at Helles in January 1916).

Scimitar Hill. Detail from: Map of Suvla, compiled by the Map and Survey Section, Mediterranean Expeditionary Force GHQ. Source: A collection of military maps of the Gallipoli Peninsula, G.H.Q. M.E.F, 1915; British Library, Digital Store Maps 43336.(21.); Crown Copyright, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

At the time immediately prior to the evacuation, the 40th Brigade trenches were in the centre of the 13th Division line, facing Scimitar Hill just south of Sulajik Farm [26]. The 4th Battalion, South Wales Borderers, who relieved the 5th Wiltshires on the 15th December, were the final battalion from 40th Brigade to depart from Suvla. Their regimental history describes the process of the evacuation, showing that the Wiltshires departed before them [27]:

Gradually supplies, carts, kits, surplus stores of all kinds, reserve ammunition and everything else that could be salved were conveyed to the beach and re-embarked in night. A programme was carefully worked out by the Staff, in accordance with which the battalion [the 4th SWB] relieved the Wiltshire at the firing-line on December 15th. The morning of the 19th found it and the Cheshire alone in the brigade’s trenches, the other two battalions having already embarked. Everything possible was done to make things appear quite normal, fires were lit in the usual places, men were posted up and down the lines as though the usual sentries were on duty and fired occasional shots.

[…]

Slowly the day wore on, being spent in such things as slitting the sandbags, so as to make them useless to the Turks, who were known to need them. Soon after dusk the Cheshire withdrew, leaving the S.W.B. alone in the front trenches.

[…]

The first portion of the battalion to move was the machine-gun section, which started for the beach at 7 p.m., followed an hour later by Colonel Bereford and 250 men. Three hours later 150 more under Major Kitchin stole away, leaving Captain Cahusac with 6 officers and 70 picked men to patrol the otherwise empty trenches for another two hours and a half before they in turn might retire.

[…]

At last the time came for Captain Cahusac’s party to start their three-mile tramp to the beach. The road to be followed had been carefully marked out with white flour and there was little chance of missing it. The leading party had manned the Lala Baba defences covering the place of embarkation, and when the rear-guard arrived the whole battalion was taken off on lighters and transferred to transports for conveyance to Imbros. It was 3. a.m. (December 20th) when the last of the 4th S. W.B. steamed out of Suvla Bay.”

The War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires is more succinct, but confirms the same broad timetable [28]:

17/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

Preparations for evacuation, stores sent away. Sandbags slashed. SAA [i.e. small-arms ammunition] evacuated, except 220 rounds per man.

Remarks: Evacuation.18/12/1915 – Suvla, Gallipoli

Misty and calm.

Machine gun teams and 2/Lt O’Brien’s party remains, while Battalion paraded at 6.0p.m and left rendezvous at 6.30p.m with adv. parties of 8/Chesh [8th Cheshire Regiment] and 8/RWF [8th Royal Welsh Fusiliers]. Load heavy. Arrive Lala Baba without casualties at 8p.m and embark for Mudros.19/12/1915 – Mudros West, Lemnos

Portianos Camp.

Arrive Mudros Harbour at 5.0a.m. Transferred to H.M.S. SWIFTSURE and thence to W. MUDROS. Pitched camp on arrival and drew few available stores.

Remarks: Camp.

The 5th Wiltshires returned to Gallipoli by the end of the year, landing at Helles on the 30th December 1915, but leaving the peninsula for the final time from Gully Beach on the 6th January. After a spell spent in Egypt (Port Said), they embarked in mid-February for Mespotamia, where the 13th Division would remain for the remainder of the war.

Looking at the casualty lists, it is also clear that Private Cook was not the only sixteen- or seventeen-year-old that was serving with the 5th Wiltshires. We do not have age data for all members of the battalion that died between July 1915 and January 1916, but the Gallipoli roll of honour in Paula Perry’s history of the battalion (which seems to be based on CWGC records) lists six that were seventeen years old, out of thirty-eight that were nineteen years old or younger [29]. Considering that recruits were supposed to be aged between 18 and 38, and officially could not be sent overseas until the age of 19, there seems to have been a lot of under-age soldiers serving in the battalion.

The action (or actions) during which Private Cook twice captured men at the point of the bayonet also remain obscure. The most substantial entry in the War Diary of the 5th Wiltshires that mentions the taking of prisoners relates to the capture of Damajelik Bair on the 6th August 1915 as part of the August Offensive [30]:

This position was taken with but slight opposition. Number of prisoners taken during the operations by the SWBs and WILTS is estimated at 250 (Reports agree that a number of the prisoners taken on this occasion were old men and very willing to fall into our hands.

Private Cook’s body was presumably buried prior to the evacuation, but the grave seems to have been subsequently lost. In Turkey, he is commemorated on the Helles Memorial (at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula). In the UK, his name appears on the war memorial in Holy Trinity Church, East Finchley [31].

Charles Van Humbeck:

Private Cook’s friend and comrade, Private Charles Van Humbeck survived the war. Despite (or perhaps because of) his unusual family name, however, he remains a bit of an enigma.

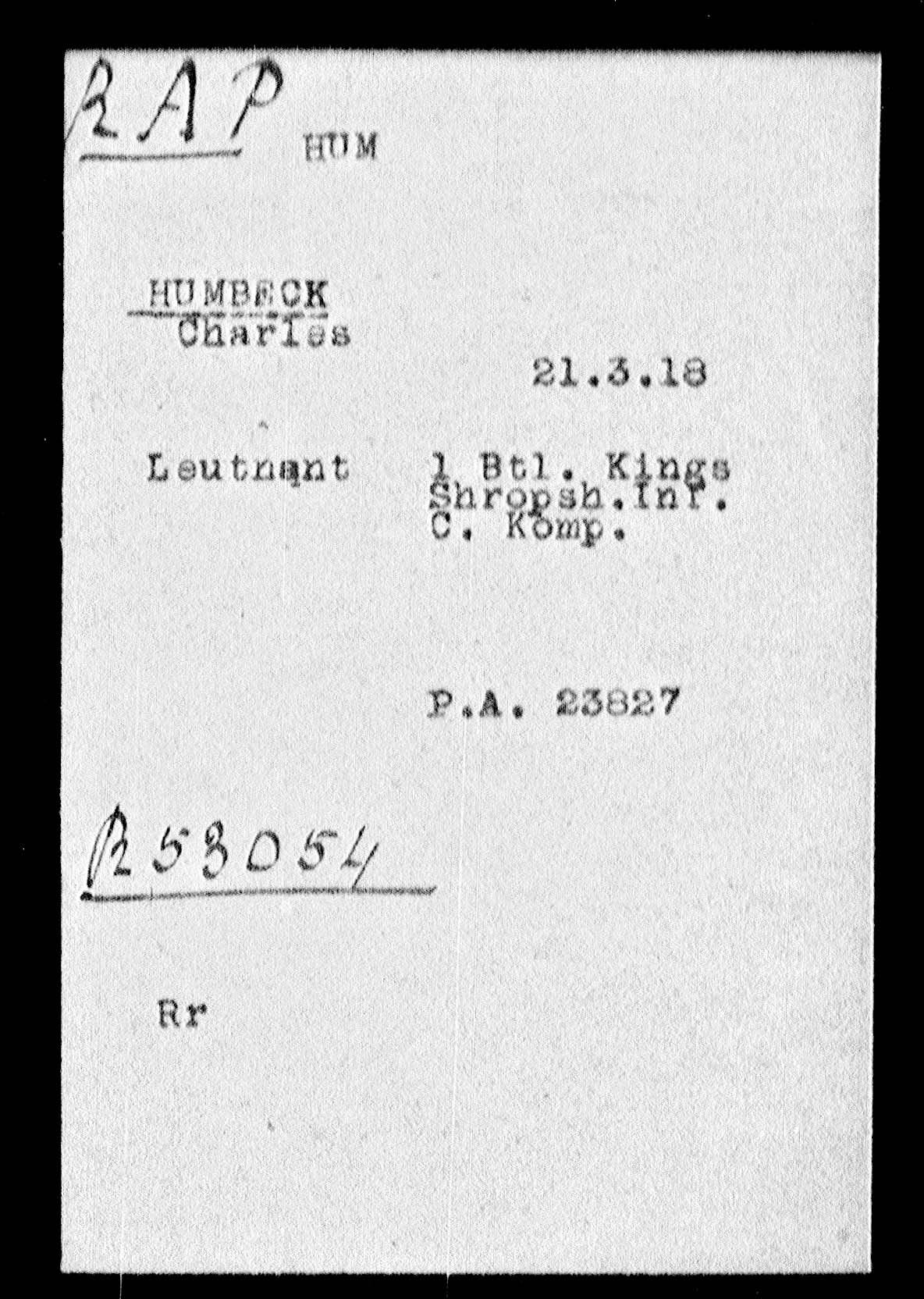

After 1915, the next mention of him that I could find was of a 9607 Pte. Humbeck of the Wilts arriving “slightly wounded” at the 4th Northern General Hospital at Lincoln on the 12 July 1916 [32]. According to his medal index card, Van Humbeck was commissioned in October 1917 [33], a fact confirmed by the London Gazette of the 28th November 1917 [34, 35]. He then went to France, where Second Lieutenant Charles Marcel Van Humbeck of the 1st Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (16th Infantry Brigade, 6th Division) was captured at Lagnicourt on the 21st March 1918, the first day of the German Spring Offensive [36]. He then became a prisoner of war in Germany, imprisoned in camps at Karlsruhe and Mainz [37, 38].

ICRC index card for 2nd Lieut. Charles Humbeck, 1st King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. Source: ICRC Historical Archives: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org

Apart from the records relating to his military service and imprisonment as a POW, Charles Marcel Van Humbeck (sometimes spelled Van-Humbeck) does not seem to feature that much in the genealogical records available via Findmypast, although he is highly-likely to be the Marcel Van Humbeeck born at Kensington (registration district) in the third quarter of 1896 (his record in the ICRC Prisoners of the First World War database states that he was born at London on the 6th July 1896). His POW record gave his home address as 90, Great Russell Street, WC., which the Kelly’s Directory from 1916 notes was also the address of “Van Humbeeck Arthur & Co. hairdressers” (a similarly named business had previously been based at 36, Fulham Road in Kensington) [39].

His name changed at least one more time. The London Gazette of the 16 January 1920 recorded that Marcel Van Humbeeck of 90 Great Russell Street had changed his name by deed poll to Charles Marcel Vann [40]. I could not find any references to him after that.

Concluding remarks:

The story of Private Cook is interesting from the perspective of his relative youth and how that was filtered through books and newspapers at the time. The fact that none of these publications managed to get his family name correct makes me wonder whether his family or former comrades actually ever knew of his posthumous “fame,” however fleeting it may have been.

Notes and references:

[1] Hendon & Finchley Times, 21 January 1916, p. 8; via British Newspaper Archive.

[2] The Dundee People’s Journal, 29 January 1916, p. 6; via British Newspaper Archive.

[3] The Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser (NSW), 7 April 1916, p. 3; via National Library of Australia (TROVE Newspapers):

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/128593776

[4] For example, I’ve found versions of the story in: The Chickasha Daily Express (Chickasha, Indian Territory, Oke), 20 April 1916, p. 4; The Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kan.), 22 April 1916, p. 13; East Oregonian (Pendleton, OR), 15 May 1916, p. 6; all via Library of Congress (Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers):

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

[5] The Seward Gateway (Seward, Alaska), 25 April 1916, p. 2; via Alaska State Library Historical Collections (Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress):

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn2008058232/1916-04-25/ed-1/seq-2/

[6] Geoff Fox, “Brave boys and girls in wartime,” Books for Keeps, issue 206: http://booksforkeeps.co.uk/issue/206/childrens-books/articles/brave-boys-and-girls-in-wartime

[7] John Lea, Brave boys and girls in wartime (London: Blackie and Son, n.d., ca. 1918).

[8] Image also available from British Library Images Online: https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/149023

[9] Findmypast: https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

[10] Essex Record Office, D/P 81/1/37, Essex Baptism Index 1538-1920; via Findmypast.

[11] Paula Perry, A history of the 5th (Service) Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment, 1914-1919 (Salisbury: Rifles Wardrobe and Museum Trust, 2007), p. 215.

[12] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary. Transcription from: The Wiltshire Regiment in the First World War: 5th Battalion, 2nd ed. (Salisbury: Rifles Wardrobe and Museum Trust, 2011), p. 25.

[13] C. E. W. Bean, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. II: The story of ANZAC from 4 May, 1915, to the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula, 11th ed. (Sydney, NSW: Angus and Robertson, 1941), pp. 699-700; digitised version of Chapter XXV available from the Australian War Memorial: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416629

For a sane appraisal of the “lost opportunity” thesis, see: Robin Prior, Gallipoli: the end of the myth (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 185-189.

[14] Bean, p. 708.

[15] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 10.

[16] Stephen Chambers, Battleground Europe: Gallipoli: Anzac — Sari Bair (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2014), p. 130.

[17] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 12.

[18] Quoted in Chambers, Gallipoli: Anzac — Sari Bair, p. 139.

[19] Peter Liddle, Men of Gallipoli: the Dardanelles and Gallipoli experience, August 1914 to January 1916 (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1988), pp. 214-215.

[20] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 10.

[21] Bean, p. 711.

[22] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 10.

[23] Western Daily Press, 20 September 1915, p. 9; North Wilts Herald, 24 September 1915, p. 6; Western Daily Press, 6 November 1915, p. 5; all via Findmypast.

[24] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 25.

[25] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 127.

[26] C. T. Atkinson, The History of the South Wales Borderers, 1914-1918 (London: Medici Society, 1931; Naval & Military Press reprint), p. 192.

[27] Ibid., pp. 191-193.

[28] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 25.

[29] Appendix 4: Gallipoli Roll of Honour, in: Perry, A history of the 5th (Service) Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment, 1914-1919, pp. 177-183.

[30] 5th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment War Diary, p. 9.

[31] Traces of War, World War I Memorial Holy Trinity Church [East Finchley]:

https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/84246/War-Memorial-WWI-Holy-Trinity-Church.htm

[32] Lincolnshire Echo, 17 July 1916, p. 1; via British Newspaper Archive.

[33] WO 372/10, British Army Medal Index Cards, 1914-1920, The National Archives, Kew.

[34] Supplement to the London Gazette, 28 November 1917, p. 12471:

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30403/supplement/12471

[35] 2/Lieut. Humbeck’s service records are in the National Archives (WO 339/93462), so I will see whether I will be able to find out any more about him from those when I am able to visit again.

[36] WO 95/1609/4, 1st Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry War Diary, The National Archives, Kew

[37] Newcastle Journal, 8 June 1918, p. 5; via British Newspaper Archive.

[38] International Committee of the Red Cross, Prisoners of the First World War: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/

ICRC index card: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en/File/Details/738710/3/2/

Gefangenenliste des Lagers Mainz, 27. April 1918: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en/List/738710/698/23827/

[39] Kelly’s Post Office Directory for London, 1916, p. 363, via Findmypast.

[40] London Gazette, 16 January 1920, p. 764:

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/31737/page/764

[…] and Trowbridge Advertiser of the 22nd January 1916, his name appearing together with the name of 9612 Private Cyril Edward Cook of the 5th Wiltshires, who had been killed in action at Gallipoli on the 15th December 1915, aged […]

By: Company Quartermaster Sergeant Simon Merritt, 6th Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment | Opusculum on December 28, 2020

at 7:43 pm