Bath: The War Memorial in Weston High Street: First World War names (Somerset)

In my previous post, I transcribed the account published in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of the dedication of the war memorials at Upper Weston (Bath) on the 17th March 1921. This supplementary post will provide some more information on the persons named on the First World War sections of the memorials. There are thirty-six First World War names on the Weston war memorial cross and thirty-eight on the panels in the war memorial chapel in the Church of All Saints.

These names were matched, where possible, with their entries in the database produced by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) [1], supplemented where necessary by with notes from the genealogical records made available by Findmypast [2] and the issues of the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette that form part of the British Newspaper Archive [3].

As is the case with many war memorials, the relatively limited information provided by the memorials (rank, initial/s, and family name) meant that it can be difficult to match a few of the names. One example on the Weston memorial was “Pte. F. Anstey.” The Bath Chronicle report from the Weston peace celebrations of August 1919 (described later in this post) lists this person as “Fredk. Anstey,” which (in theory) should have made the search easier. The genealogical databases showed that there was a Frederick George Anstey living in the Bath area at the appropriate time (he was born at Batheaston in 1885, and the 1911 Census recorded him at Bangalore with B Squadron of the 14th King’s Hussars). However, the electoral registers in Findmypast also showed that this Frederick survived the war (he died at Bath in 1953, aged 68). Fortunately, there was a likely alternative identification in the CWGC database: Private Alfred Richard John Anstey of the 2nd Royal Marine Battalion, who was killed in action near Passchendaele on the 26th October 1917. His link with Weston was confirmed by the additional information in his CWGC database entry: “Son of Alfred and Sarah Anstey, of 65 High St., Upper Weston, Bath,” as well as the fact that he enlisted (and died) on the same day as another Weston resident, Private James Edwin Holbrow. Evidently, Alfred was known to some as Fred or Frederick. I have been unable to identify two of the persons named on the memorial. Privates H. Frankham and T. Marshall both defeated my searches and both feature at the end of my list.

Lists of Weston casualties started to appear in the Bath Chronicle during the war itself. A longer list was then published in the Chronicle’s account of the Weston Peace Celebrations on the 26th July 1919 [4]. The day commenced with some bellringing:

At seven o’clock the ringing of the church bells proclaimed the coming of the festal day, and at one o’clock another peal was rung. At 1.15 the procession assembled at the village green in readiness for the open-air service at the Recreation Ground, for it was rightly intended that the rejoicings should begin by an act of remembrance of the gallant dead. The procession was headed by one of Weston’s heroes, Lieutenant W. Anstey, R.A.F., who lost a leg in the fighting at Hill 60, but after recovering from his wound obtained a commission in another branch of the service. His cousin is numbered among the fallen parishioners. Lieutenant Anstey led the procession on horseback.”

The service at the Recreation Ground included the singing of “O God, our help in ages past” and “Old Hundreth.” Then the Vicar (Rev. F. A. Bromley) read the name of twenty-eight parishioners who had died:

William Old

Vernon and Reginald Newman

William Perry

Frederick Blackmore

Frank and Arthur Pickett

William, George and Ernest Bond

Charles, Alfred, Ernest and Walter Lewis

William and Ernest Humphris

Fredk. Gillard

Fredk. Anstey

Arthur Graham Johnston

Reginald Bourne

Albert Hawkins

James Edwin Holbrow

Arthur Richards

William George Kite

Harry Nash Russell

John Sheppard

William Hobbs

Alfred Gillard

After singing the National Anthem, the procession moved on to the Manor Park field, where there was a programme of sports events, performances by the “Comrades” Band, a fancy-dress competition, tea (of course!), and an evening dance.

Another peal by the ringers gave tidings of the ending of a day memorable in Weston’s parochial annals.

A glance at RAF Officers’ Service Records 1912-1920 (via Findmypast) shows that Lieutenant W. Anstey was William Robert Douglas Anstey, the son of Arthur Robert and Annie Anstey. Before joining the RNAS, he had been a Sapper with the 2nd (Wessex) Company, Royal Engineers.

As the list of names might suggest, the memorials commemorate at least five sets of siblings. Frederick Lewis, a widower living at 9, Manor Road, lost four sons: Charles Henry on the Somme in 1916, Alfred near Epehy in October 1918, and both Ernest and Walter James after the Armistice (of influenza). Priscilla Bond of No. 2, Moravian Cottages (but formerly of Church Road, Weston), who had herself been widowed when her husband Thomas W. Bond died in 1915, aged 57, lost three of her four adult sons to the war. Thomas (the eldest) survived, being awarded the Military Cross twice and the Croix de Guerre, while the others were not so fortunate: William died in 1917, and then both George and Ernest in 1918. Two of the officer sons of Olinthus and Mary Newman would also be killed in action: Vernon William at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, Reginald Bodman on the Somme almost exactly a year later (Olinthus Newman himself was killed in 1918, the casualty of a tram accident in Lower Weston). Henry William and Sarah Humphris (sometimes Humphries) of 29, Trafalgar Road lost two sons, Henry and Ernest, who died respectively on the Somme in 1916 and at Arras in 1917. Both of the sons of George and Emma Pickett of 26, Church Road also died: Frank being drowned in the Mediterranean in April 1916, while Arthur Sidney was killed by an exploding shell near Ypres in October 1917. Finally, Robert and Selina Gillard of 4, Westbrook Buildings lost two of their sons, Alfred Edward and Frederick, who were both killed in action near Arras in May 1917.

As has already been mentioned, both Alfred Anstey and Edward Holbrow (sometimes known as Edwin or James Edwin Holbrow) enlisted in the Royal Marine Light Infantry on the same day. They had adjacent service numbers and identical service records. Both were killed in action near Passchendaele on the 26th October 1917, aged 19. Both have no known grave and are commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial. Both of their families lived in Weston High Street.

Of the thirty-six casualties that I have been able to identify, just three were buried in cemeteries in the UK: Private John Sheppard, at Bath (the Weston section of Locksbrook Cemetery) and Privates Ernest and Walter James Lewis at Chepstow. All three had previously served overseas. The overwhelming majority of those named on the memorials died on the Western Front, including twenty buried or commemorated in France and another nine in Belgium (West Flanders). Four others are commemorated or buried at locations in Turkey, Iraq, Greece, and Israel/Palestine.

There are several different potential ways of organising the names on a war memorial. Both of the Weston memorials are sorted by military rank and then family name, although there are a few inconsistencies. In this post, I have listed them in the date order of their deaths, as this gives an idea of the war’s progress. If I have found an associated report in the Bath Chronicle, I have also transcribed that. The information is based on that provided by the CWGC database, but it has been selectively supplemented with information from the Findmypast service, including: the Soldiers Died in the Great War database, census returns, electoral registers, and BMD records. The entries are really collections of notes rather than fully-rounded portraits of the individuals involved, but I hope that they collectively help paint a picture of Upper Weston at the time of the First World War. At some point I will try to map out the names in geographical space. For those that do not want to wait, please do look at A Street Near You, where you will be able to find the names of a good many more First World War casualties with links to Upper Weston: https://astreetnearyou.org/

Researching the names on war memorials is not an exact science. It is likely, therefore, that the entries in this post will contain misidentifications, errors, and omissions. I would like to apologise for any mistakes in advance, and will try to correct them when they come to light.

May they all Rest in Peace.

1915-1916

There were nine casualties from the start of the war to the end of 1916, seven of them on the Western Front, one at Gallipoli, and another one killed when his hospital ship hit a mine near Le Havre. The first man from the village to die was Driver William Old of the Wessex Engineers, who was killed in action on the 6th May 1915, aged 44. Four would die in the campaign on the Somme, three of whom have no known grave and are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing. The nine include two sons of Councillor Olinthus Newman of Combe Park, who himself would be killed tragically at Bath in a tramway accident on the 29th May 1918 [5].

Driver William Old, Royal Engineers

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 8 May 1915, p. 7; via British Newspaper Archive.

Driver William Old, 1st (Wessex) Field Coy., Royal Engineers; Service No. 959

Died of wounds 6 May 1915, aged 44

St. Sever Cemetery, Rouen (A. 9. 6.), Seine-Maritime, France

CWGC additional information: Son of Charles and Sarah Ann Old, of Weston; husband of Matilda Elizabeth Old, of 2, Lansdown View, Weston, Bath

Born: ca. 1872

1881 Census: 1 Bond’s Cottages, Weston, Bath; aged 9, scholar; household of Charles Old, aged 35, carter; son of Charles and Sarah Old

1891 Census: Bonfield Cottages, High Street, Weston, Bath; aged 19, cab driver; household of Charles Old, aged 45, cab proprietor; son of Charles and Sarah Old

Married: Matilda Elizabeth Wake, Bath (registration district), 1st Q, 1895

1901 Census: 2 Lansdown View, Weston, Bath; aged 29, cabman; married to Matilda E. Old, aged 28, laundress; two children: Charlie, 5; William, 3.

1911 Census: 2 Lansdown View, Weston, Bath; aged 39, fly proprietor (on own account); married to Matilda Old, aged 38, laundress; two children: Charlie Old, 15, engineer’s fitter; William Old, 13, at school.

Widow: Matilda E. Old, died Bath (registration district), 2nd Q, 1958, aged 85

Bath Chronicle and Monthly Gazette, 8 May 1915, p. 7:

ANOTHER WESSEX HERO

DRIVER W. OLD DIES OF WOUNDS

It will be heard with deep regret that Driver William Old, of the 1st Wessex Royal Engineers, died from wounds in a military hospital at Rouen on Thursday afternoon.

On Wednesday his wife had received official information that her husband had been wounded. On Thursday came a telegram from the military authorities that he was “severely wounded” and to-day came the notification by wire that he succumbed to his injuries as stated. Few people were better known in Bath than the deceased. He was a popular cheery cab proprietor and generally stood at the bottom of Gay Street or at Edgar Buildings. For many years he was invariably accompanied by an Aberdeen terrier as the mascot of his cab; and when the old favourite died, a lady patroness kindly presented Mr. Old with another dog of the same breed. On the outbreak of war, Mr. Old patriotically offered his services, setting a spirited example to younger men; and on account of his special skill among horses, he was accepted and joined the Wessex Engineers as a driver, though it was no secret that he was well over the stipulated maximum age. He has a son also in the Wessex R.E., but he has not gone to the front yet, and is in Dorset. Another son is an employee of Messrs. Stothert and Pitt and is away from Bath on the firm’s work. How Driver Old was wounded is not known.

A letter from Sapper Richardson, of Bathwick, given in Thursday’s “Chronicle,” stated that he helped to carry the wounded man to the field hospital. In his last letter to his wife Mr. Old wrote as if he had a premonition of his impending fate. Mrs. Old, who lives at 2 Lansdown View, Upper Weston, will receive sincere sympathy in her bereavement. She was a Miss Wake, of Weston, and her mother recently died at the home of another daughter, Mrs. Thomas, in the Upper Bristol Road. Mr. Old for some years was a member of the Weston Parish Council.

Private William Slee, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

Private William Slee, 9th Bn., West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Own); Service No. 15629

Killed in action, 9 Aug 1915, aged 22

Helles Memorial (Panel 47 to 51.), Turkey

CWGC additional information: Son of James Slee, of 5, The Grove, Weston, Bath, and the late Isabel Slee

Born: Sunderland (registration district), 1st Q, 1892, son of James Slee and Isabel Slee (née Blenkinsop)

1891 Census: Devonshire Street, Monkwearmouth (Co Durham); James Slee, aged 26, steam engine maker; Isabella Slee, aged 22; John Slee, aged 8 mths

1901 Census: 42 Jacques Street, Sunderland; William Slee, aged 9; household of James Slee, aged 36, steam engine maker (turner)

1911 Census: 50 Tilery Road, Stockton-on-Tees; William Slee, aged 19, boiler rivetter; household of John Robert Cowan (uncle), aged 35, police constable

1911 Census: 9 Davis Street, Avonmouth, Bristol; James Slee, boarder, aged 47, widower, engineer / engine fitter; household of Frank Edwin Blake, aged 40, coal merchant

Soldiers Died in the Great War: Enlisted at Stockton-on-Tees (Co Durham).

Captain Vernon William Newman, 4th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment:

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 4 September 1915; via British Newspaper Archive.

Captain Vernon William Newman, 4th Bn., West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Own), attd. 1st Bn., The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Killed in action, 25 Sep 1915, aged 30

Dud Corner Cemetery, Loos (III. F. 16.), Pas-de-Calais

CWGC additional information: Son of Olinthus and Mary Newman, of Lathom House, Weston Park, Bath

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 October 1915, p. 3:

CAPTAIN V. W. NEWMAN KILLED IN ACTION

ELDEST SON OF MR. COUNCILLOR NEWMAN

We regret to hear that Captain Vernon W. Newman, eldest son of Mr. Councillor O. Newman, of Winfield, Combe Park, has been killed in action in France. The sad news has reached Mr. Newman in a telegram from the War Office which says that Captain Newman was killed on the 26th or 27th September and expresses the sympathy of Lord Kitchener with the deceased officer’s family. Captain Newman, who was 31 years of age, was educated at King Edward’s School, Bath, and adopted electrical engineering as his profession; he took the degree of B.Sc. at London University and was on the staff of the Central Engineering College, South Kensington, which is attached to the University. That institution he left for a technical appointment under the government and he was so engaged when war broke out. He then obtained a commission in the 4th West Yorkshire Regiment. Attached to the Loyal North Lancashires, he went to France several months ago, had seen considerable fighting with that regiment and was promoted to command a company. He was in Bath about a fortnight ago, when he came home for a few days’ leave from the front. Deep sympathy will be felt with Councillor and Mrs. Newman, who have two other sons, officers in HM Army, one being at the Dardanelles and the other in England.

The 1st Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment was part of 2nd Brigade in the 1st Division. In the War Diary of the 1st Loyal North Lancashires, Captain Newman is one of nine officers listed as being killed on the 25th/26th September, during the Battle of Loos.

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Private William Perry, 2nd Battalion, Suffolk Regiment

Private William Perry, 2nd Bn., Suffolk Regiment; Service No. 15667

Killed in action, 20 Mar 1916

Voormezeele Enclosures No. 1 and No. 2 (I. D. 7.), West Vlaanderen, Belgium

Born William Frederick Perry, 2nd Q, 1882

1891 Census: Elphage Place, Weston; aged 9, mason’s labourer; son of Charles (a gas stoker) and Eliza Perry

WO 97, Chelsea Pensioners British Army Service Records 1760-1913, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

Enlisted in the 4th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, 14 July 1899, aged 18

5223 Attested 7 Nov 1898, 4th SLI

5558 Somerset Light Infantry

Born Upper Weston

Labourer

Deserted, left 29 Apr 1901 (after trial)

1911 Census: 6 Penhill Terrace, Upper Weston; aged 29, gas stoker; married to Eileen, 29, laundress; married for four years, with two children.

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born: Weston, Somerset; enlisted: Greenwich

Second Lieutenant Reginald Bodman Newman, Machine Gun Corps (Infantry)

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 4 September 1915, p. 3; via British Newspaper Archive.

Second Lieutenant Reginald Bodman Newman, 168th Coy., Machine Gun Corps (Infantry)

Killed in action, 7 Sep 1916, aged 29

Thiepval Memorial (Pier and Face 5 C and 12 C.), Somme

CWGC additional information: Son of Olinthus and Mary Newman, of Weston Park, Bath, Somerset

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 16 September 1916, p. 6:

LIEUT. R. B. NEWMAN KILLED IN ACTION

BATH COUNCILLOR’S SECOND BEREAVEMENT

Councillor and Mrs. O. Newman, of 33, Combe Park, Weston, have received the news of the death of their second son, Lieut. Reginald B. Newman. The telegram from the Secretary to the War Office stated that Lieut. R. B. Newman, Machine Gun Corps, was killed in action in France on September 7th.

Lieut. R. B. Newman was educated at King Edward’s School, Bath, and subsequently entered the engineering profession, being trained at the works of a local firm. At the conclusion of his pupilage he worked for a short time at Yeovil. Leaving there, he accepted a position on important constructional work in Vancouver, B.C., where he remained for a period of five years.

Shortly after the outbreak of war he enlisted, and within a short time obtained his commission in the 4th West Yorks Regiment, Special Reserve. Lieut. R. B. Newman’s elder brother, the late Captain V. W. Newman, had previously obtained his commission in the same regiment. Soon after the death of Captain Newman, who was killed in action in September of last year, Lieut. R. B. Newman, who had specialised in machine gunnery, was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, and while working in France with this Corps, the late officer met his death.

Councillor and Mrs. Newman have had three sons at the Front, and deep sympathy will be felt for them in their double loss. The third son, Lieut. B. O. Newman, R.F.A., has been on the Salonika front during the past twelve months.

The 168th Company, Machine Gun Corps was part of 168th Infantry Brigade in the 56th (1st London) Division. On the 6th September 1916, the Division was based in the area around Leuze Wood, near Guillemont, on the Somme front.

The War Diary of 168 Coy, MGC recorded that Second Lieutenant R. B. Newman was killed in Leuze Wood at 11:30 pm on the 7th September 1916, in the lead up to an attack of 168th Brigade on the 9th September. It was during this attack by 168th Brigade on the 9th September that Major Cedric Charles Dickens of the 1/13th London Regiment (1st Kensingtons Battalion), a grandson of the writer Charles Dickens, was killed in action. The 9th September attack was one of several made preparatory to the renewal of the Somme offensive on the 15th September. On the 15th, the 56th Division was detailed to capture defences around Bouleaux Wood and form a defensive flank around Combles.

Second Lieutenant Newman’s two younger brothers both served, but would survive the war. Captain Bruce Olinthus Newman served with the Royal Field Artillery, but was later attached to the Royal Air Force (RAF). Lieutenant Christopher Baldwin Newman served with the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Air Force. Tragically, Olinthus Newman was killed in a tram accident near the Weston Hotel on the 29 May 1918. He was travelling on the (open) upper deck of the tram when the driver lost control and the tram overturned. Councillor Newman was thrown into the road and he died in the Royal United Hospital the same day, without regaining consciousness. His grave marker in Locksbrook Cemetery contains the names of the two sons that died during the war.

Driver Frederick William Blackmore, Canadian Field Artillery:

Driver Frederick (Fred) William Blackmore, 2nd Div. Ammunition Col., Canadian Field Artillery; Service No. 86246

Died of wounds, 27 Oct 1916, aged 40

Contay British Cemetery, Contay (III. D. 20.), Somme, France

CWGC additional information: Son of Robert (and Sarah) Blackmore, of 27, Church Rd., Upper Weston, Bath.

Robert Blackmore (father) married Sarah Perry, Holy Trinity Church, St Philip’s, Bristol, 12 May 1870 (Marriages, 1867-1871, Bristol Archives; via Findmypast)

Frederick William Blackmore, baptised St John the Baptist, Frenchay, 29 Jun 1879 (Baptism Transcripts, 1834-1907, Bristol Archives; via Findmypast)

1881 Census: 5, Westbourne Cottages, Winterbourne, Barton Regis, Gloucestershire; Frederick W. Blackmore, aged 2, born Frenchay; resident with Robert Blackmore (32, gardener, born Wellington, Somerset) and Sarah Blackmore (30, born Bradford-on-Tone, Somerset); four older siblings: Samuel H. (9, scholar), Ellen (8, scholar), Edith (7, scholar), and Robert E. (3, scholar), all born at Fishponds, Bristol

1891 Census: Upper Church Place, Weston, Bath; Frederick Blackmore, aged 11 (scholar); resident with Robert Blackmore (42, domestic servant gardener) and Sarah Blackmore (41); three siblings: Edith (17, domestic servant, born Fishponds), Elizabeth (9, scholar, born Frenchay), Florence (6, scholar, born Weston).

WO 128, Imperial Yeomanry, Soldiers’ Documents, South African War 1899-1902, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

Enlisted in the Imperial Yeomanry, Bath, 19 Feb 1901, aged 21

Trade on attestation: Gardener

Service no: 27340; 7th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry, 48th (N Somerset) Company

Served in South Africa 16 Mar 1901 – 4 Aug 1902

Discharged Aldershot, 11 Aug 1902

FWW Service records available from Library and Archives Canada (Ref. RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 786 – 38.; B0786-S038):

Birth: Bath, 11 Apr 1880 [this does not match the information provided by other records]

Next-of-Kin: Robert Blackmore (father), 27 Church Road, Bath

Enlisted: Winnipeg, Manitoba, 24 Dec 1914

Trade on attestation: Steam Fitter

Previous military experience: 12 years in North Somerset Rif. (presumably the North Somerset Yeomanry)

1st Reserve Battalion, 5th Artillery Brigade

Embarked for France from UK: 18 Jan 1916

Served as Gunner with 6th Howitzer Brigade, Canadian Expeditionary Force; posted to 2nd Canadian Divisional Artillery Column, 20 May 1916

Admitted 11th Canadian Field Ambulance, 25 Oct 1916, then 49 Casualty Clearing Station (Contay) 27 Oct 1916 (gunshot wound, left thigh and back)

War Diary of Divisional Ammunition Column, 2nd Canadian Division, Library and Archives Canada (Ref. RG9-III-D-3. Volume/box number: 4978. File number: 584.)

Entry for 26 Oct 1916 (HQ at Albert W.24.a.4.7.):

Issued ammunition noon 25th to noon 26th A 5-305, AX 6504, BX 1152. No. 7699 Dvr LEVERTON J. killed, No. 86246 Dvr BLACKMORE F. seriously wounded, No. 87169 Gnr HEMMING A. seriously wounded, No. 64 Dvr CARSON J.H. wounded all by shell fire while taking up ammunition about X.3.a.3.5. Owing to heavy mud in tramway and lack of proper ballast the line had to be abandoned. Instead amm. is now taken from Tramway Terminal to batteries by pack horses, each horse carries 8 rounds of 18 Pdr. in the baskets from amm. Wagons or 4 rounds 4.5 in the amm. Boxes. The work is heavy and the sticky mud results in many shoes being pulled off.

Map ref X.3.a.3.5. (Sheet 57D.SE.4) is near the track that links the village of Ovillers with the road running north-west from Pozières to Thiepval (the current D73).

On the 1st October 1916, the 2nd Canadian Division had attacked and failed to capture Regina Trench, a long trench system that ran from around Le Sars to Grandcourt. On the 21st October, the 2nd Canadian Divisional Artillery operated in support of the 4th Canadian Division and the 18th (Eastern) Division in a more successful attack on the same trench system. There was a smaller-scale attack by the 4th Canadian Division on the 25th, but bad weather then led to the postponement of further major operations until the 9th November.

Driver Jack Leverton is buried in Bapaume Post Military Cemetery, near Albert.

Private Joseph Toogood, Royal Army Medical Corps

Private Joseph Toogood, Royal Army Medical Corps, attd. H.M.H.S. Galeka; Service No. 52913

Died at sea (HMHS Galeka), 28 Oct 1916, aged 34

Ste. Marie Cemetery, Le Havre, Seine-Maritime, France (Galeka Memorial)

HMHS Galeka was Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company ship requisitioned for use as a troop transport and hospital ship. She hit a mine when entering Le Havre on the 28 October 1916: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Galeka

Rifleman Charles Henry Lewis, 21st Battalion, London Regiment (First Surrey Rifles)

Rifleman Charles Henry Lewis, 21st Bn., London Regiment (First Surrey Rifles); Service No. 7145

Killed in action, 14 Nov 1916

Thiepval Memorial (Pier and Face 13 C), Somme

CWGC additional information: Son of Frederick Lewis, of 9, Manor Rd., Upper Weston, Bath; husband of Amy Lewis, of 63A, Inglethorpe St., Fulham Palace Rd., Fulham, London.

Born: 4th Q, 1887

1891 Census: Manor Road, Weston, Bath; Henry C. Lewis, 3, Son of Frederick M. Lewis and Jane E. Lewis

1901 Census: Highbury, Bodorgan Road, Bournemouth (St Stephen), now Bodorgan Court; Charles H. Lewis, 13, servant, page; part of household of Catherine Thompson

1911 Census: Swinfen Hall, near Lichfield, Staffordshire; Charles H. Lewis, 25, servant, footman domestic; also Amy Crusher, 32, servant, housemaid domestic, b. Welbury, Yorks

Marriage: Amy Crusher, Fulham, 2nd Q, 1915 (born Northallerton, North Riding, 1879)

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born: Bath; residence: Fulham; enlisted: West London; formerly 6424, 23rd London Regiment, posted 1st Bn., Royal Irish Rifles

There is a slight mystery here. The 1/21st London Regiment were part of 142nd Infantry Brigade in the 47th (2nd London) Division. While the 47th Division had been involved in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette in September 1916, and had remained on the Somme front until mid-October, by November they were recuperating in the Ypres sector. The battalion War Diary (WO 95/2732/5) for November 1916 is not that detailed, but it shows that the 1/21st Londons were either behind the lines training and refitting at Busseboom (Scottish Camp), in support or reserve at Railway Dugouts or Woodcote Farm, or in the front line facing Hill 60 or on the Bluff, reporting no casualties at all for the month. If Rifleman Lewis had been killed in action near Ypres, it would seem a little odd for him to have been commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, so it seems likely that he remained on the Somme front. A possible answer is suggested by Rifleman Lewis’s entry in Soldiers Died, which is replicated verbatim in the Roll of Honour published in A War Record of the 21st London Regiment [6]:

Lewis, Charles Henry, b. Bath, e. West London (Fulham), 7145, Rfn., k. in a., F. & F., 14/11/16, formerly 6424, 23rd London Regt., posted 1st Bn. Royal Irish Rifles.

The 23rd London Regiment probably refers to the 1/23rd Battalion, who like the 1/21st were also part of 142nd Brigade in the 47th Division. It is possible, however, that Rifleman Lewis was drafted from one of the other battalions of the 23rd (County of London): the 2/23rd Battalion, who were with 60th (London) Division (who served on the Western Front from June until November 1916, before moving to Salonika and Palestine), or the 3/23rd, who remained on the home front throughout the war.

In late 1916, the 1st Royal Irish Rifles formed part of 25th Infantry Brigade in the 8th Division. Unlike the 47th Division, the 8th were still based on the Somme in November 1916, fighting in the area around Le Transloy. According to the War Diary of the 1st Royal Irish Rifles (WO 95/1730/4), the battalion relieved the 2nd Royal Berkshire Regiment in the right sector, left sub-section, opposite Le Transloy on the 13th November. It noted that the battalion front was shelled with gas shells, reporting that nine other ranks were wounded on the 13th, and four killed and three wounded on the 14th November. One of those killed on the 14th is likely to have been Rifleman Lewis.

[Comment added August 11, 2023: the CWGC database notes that Rifleman 7117 William Henry Narraway of the 21st Bn., London Regiment (First Surrey Rifles), who died on the day after Rifleman Lewis, had also been posted to the 1st Bn, Royal Irish Rifles. A War Record of the 21st London Regiment also noted that Rfl. Narraway had previously served with the 23rd Bn., with a Service Number very close to that of Rfl. Lewis (6427).]

Rifleman Lewis is one of four brothers named on the memorial.

Sergeant Henry William Humphris, 11th Battalion, Border Regiment

Serjeant Henry William Humphris (or Humphries), 11th Bn., Border Regiment; Service No. 13866

Killed in action, 18 Nov 1916

Thiepval Memorial (Pier and Face 6 A and 7 C.), Somme

Born: Bath, 3rd Q, 1886

1891 Census: Richmond Place, Bath; aged 4; son of Henry William Humphries (a lamplighter) and Sarah L. Humphries

1901 Census: 8 Fountain Buildings, Bath; aged 14, pupil teacher; son of Henry W. Humphries (Army Pensioner) and Sarah L. Humphries

1911 Census: 47 Hibbert Street, Luton, Bedfordshire; Henry Wm. Humphris, aged 24, assistant school master; boarder at the household of Sarah Howe (retired housekeeper)

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born: Bath; residence: Barnsley, Yorks, enlisted: Appleby, Westmorland

WO 363, First World War Service Records ‘Burnt Documents’, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

11/13866, XI (Lonsdale) Battn., Border Regt

Born: Bath, 1886

Trade / Calling: schoolmaster

Wife: Ethel, née Sidebottom, married Luton, 28 Feb 1912

Enlisted: Appleby, 17 Oct 1914, aged 28

Appointed Lce Cpl 8 Dec 1914

Promoted Corpl 26 Feb 1915

Appointed Lce Sgt 3 Jun 1915

Promoted Sgt 5 Oct 1915

The 11th (Service) Battalion, Border Regiment was known as the Lonsdale Battalion as it was raised as a ‘pals’ battalion in Cumberland and Westmorland by the 5th Earl of Lonsdale. It’s first commander was Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Wilfrid Machell, CMG, DSO. They were part of 97th Infantry Brigade in the 32nd Division. The battalion suffered many casualties when they attacked the Leipzig Salient, near Thiepval, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the 1st July 1916. The casualties included Lieut.-Col. Machell. On the 18th November, the battalion were back on the Somme front, in the Redan sector north of the River Ancre between Beaumont-Hamel and Serre (Waggon Road).

One of two brothers named on the memorial

1917

Sixteen men from the village died in 1917, the vast majority of them while serving on the Western Front. While Private John Sheppard is buried in Locksbrook Cemetery, he had been wounded in France. Of the fourteen killed or wounded on the Western Front, at least three seem to have died during the Battle of Arras in the Spring, while another seven died in various parts of the long campaign in West Flanders known as the Third Battle of Ypres. The only two that were not serving on the Western Front at the time of their death, Lieutenant-Colonel Haldane Burney Rattray and Private Frank Pickett, died in Mespotamia and the Mediterranean.

Rifleman Harry Nash Russell, 1/12th Battalion, London Regiment (The Rangers)

Rifleman Harry Nash Russell, 1/12th Bn., London Regiment (The Rangers); Service No. 471468

Killed in action, 28 Jan 1917, aged 27

Loos Memorial (Panel 131), Pas-de-Calais

CWGC additional information: Stepson of Mrs Alice L. Russell, 84 High St., Weston, Bath

1911 Census: Trafalgar Road, Weston; Harry Nash Russell, aged 21, working as bookbinder; son of Joseph Russell (a carpenter and builder) and Alice Russell

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born: Upper Weston, residence Hammersmith; enlisted London

Lieutenant-Colonel Haldane Burney Rattray, DSO, 45th (Rattray’s) Sikhs

Lieutenant Colonel Haldane Burney Rattray, DSO, 45th (Rattray’s) Sikhs

Killed in action, 1 Feb 1917, aged 46

Basra Memorial (Panel 56), Iraq

CWGC additional information: Son of the late Col. Thomas Rattray, C.B., C.S.I., and Harriet Penelope Rattray; husband of Effie Watson (formerly Rattray), of Cheltenham

Name only features on the memorial in the Church of All Saints

Lieutenant-Colonel Rattray was the subject of a detailed post on this blog earlier this year.

Bombardier Ernest George Humphris, Royal Garrison Artillery

Bath Chronicle, 7 April 1917, p. 10; via British Newspaper Archive.

Bombardier Ernest George Humphris (or Humphries); Service No. 91072

260th Siege Bty., Royal Garrison Artillery

Killed in action, 22 Mar 1917, aged 29

Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras (II. J. 18), Pas-de-Calais

CWGC additional information: Son of Henry and Sarah Humphris; husband of Ethel May Humphris, of 12, Westhall Rd., Lower Weston, Bath. Headmaster of Englishcombe, Bath. Born at Bath.

1891 Census: Richmond Place, Bath; Ernest G. Humphries, aged 3; son of Henry William Humphries (lamplighter) and Sarah L. Humphries

1901 Census: 8 Fountain Buildings, Bath; Ernest G. Humphries, aged 13, postal telegraph messenger

1911 Census: 29 Trafalgar Road, Upper Weston, Bath; Ernest Humphris, aged 23, certificated teacher, son of Henry and Sarah Humphris

Married: Ethel May Pearce, Bathwick, 1912

Soldiers Died in the Great War: residence: Englishcombe, Somerset; enlisted: Bath

Also commemorated on the Englishcombe war memorial

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Private Frank Pickett, 1st Garrison Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

Private Frank Pickett, 1st Garrison Bn., Devonshire Regiment; Service No. 59191

Died, 15 Apr 1917

Mikra Memorial, Greece

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born Bath; enlisted Weston-super-Mare

Born: Frank Ernest Pickett, 3rd Q, 1880

1881 Census: Whitley Cottage, Primrose Hill, Weston, Bath; aged 8 mths, son of George and Emma Pickett

1891 Census: Whitley Cottage, Primrose Hill, Weston; aged 10, at school

1901 Census: 34, Primrose Hill, Weston; aged 20, gardener

1911 Census: 26 Church Road, Upper Weston; Arthur Pickett, aged 30, gardener in private family; son of George Pickett (gardener in private family) and Emma Pickett; the youngest of four children then resident

Drowned in the Mediterranean Sea; his brother Arthur also died

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Air Mechanic Second Class William James Bond, Royal Flying Corps

Bath Chronicle, 16 December 1916, p. 11; via British Newspaper Archive.

Air Mechanic 2nd Class William James Bond, 70th Sqdn., Royal Flying Corps; Service No. 77683

Died 24 Apr 1917

Honnechy British Cemetery (I. B. 23.), France

Concentrated from Bantouzelle Coml Cemetery Ger Ext (57b.M.26.b.4.4.)

Buried next to 2/Lt C. H. Halse, 70 Sqdn, RFC (South Africa)

Born: Bath, 3rd Q, 1894

1901 Census: 5 River Terrace, Weston, Bath; aged 7

1911 Census: Sunnylands, Audley Park Road, Weston; aged 16, servant domestic; household of Caroline Gertrude Scudamore

One of four brothers, three of whom are named on the memorial

Also commemorated on the City of Bath war memorial.

Private Alfred Edward Gillard, 7th Battalion, Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment

Private Alfred Edward Gillard, 7th Bn., Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment); Service No. G/24554

Killed in action, 3 May 1917, aged 29

Arras Memorial (Bay 7.), Pas-de-Calais

CWGC additional information: Son of Robert and Selina Gillard, of 4, Westbrook Buildings, Upper Weston, Bath; husband of Alice Gillard, of Green Lane, Hinton Charterhouse, Bath

1911 Census: 127 High Street, Weston; Alfred Gillard, aged 22, bread baker; son of Robert Gillard (mason’s labourer) and Selina Gillard (laundry worker); one of six children resident

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born Weston, Som; enlisted Lydney, Glos

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Private Arthur Richards, 1st Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

Probably:

Private Arthur Richards, 1st Bn., Devonshire Regiment; Service No. 318281 (or 3/8281)

Killed in action, 9 May 1917

Arras Memorial (Bay 4)

Soldiers Died in the Great War: 3/8281 1st Devonshire Regiment; born: Taunton; enlisted: Bath

Born Taunton, 2nd Q, 1887

Baptised Holy Trinity, Taunton, 10 May 1887, son of Charles Richards (Colour Sergeant, 4th Battation, Somersets) and Maria Richards, of 61 South Street, D/P/TAU HT 2/1/2, Somerset Baptism Index, Somerset Archives; via Findmypast

1891 Census: Walcot Street, Bath; aged 4; son of Charles (a soldier) and Maria Richards

1901 Census: 12, Osborne Road, Weston; aged 14, errand boy

WO 97, Chelsea Pensioners British Army Service Records 1760-1913, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

7404 Devonshire Regiment

Attested Bristol, 25 June 1903, aged 18

Posted 2nd Battalion, 15 October 1903; joined at Exeter

Discharged 7 October 1904, after several spells of imprisonment (deemed “incorrigible and worthless”)

Private Frederick Gillard, 16th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

Private Frederick Gillard, 16th Bn., Middlesex Regiment; Service No. TF/202420

Killed in action, 23 May 1917, aged 34

Arras Memorial (Bay 7.), Pas-de-Calais

1911 Census: 127 High Street, Weston; Alfred Gillard, aged 28, dairy farmer; son of Robert Gillard (mason’s labourer) and Selina Gillard (laundry worker); one of six children resident

Soldiers Died in the Great War: residence Bath; born Weston; enlisted Taunton

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Private John Sheppard, 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry

Private John Sheppard, 1st Bn., Somerset Light Infantry; Service No. 34218

Died of wounds (Sheffield), 31 May 1917, aged 28

Bath (Locksbrook) Cemetery (Western G. 784.)

CWGC additional information: Husband of Elsie F. Sheppard, of 105, High St., Weston, Bath.

Formerly served in the North Somerset Yeomanry (Service No. 575)

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born and resident at Weston, Bath

During April and May 1917, the 1st Somersets had been involved in the Battle of Arras (the attacks on the Hyderabad Redoubt in April and on Roeux in early May) and it seems likely that Private Sheppard was wounded in one of those actions.

Burial report in Bath Chronicle, 9 June 1917, p. 13:

MILITARY FUNERAL AT LOCKSBROOK

Much interest was evinced in the military funeral at Locksbrook on Wednesday of Private John Sheppard, Somerset L.I., who died of wounds at a military hospital in Sheffield on Thursday in last week. The Rev. F. A. Bromley officiated. The chief mourners were the widow, Mrs. Sheppard, Miss Sheppard, Mr. Harry Sheppard, Mrs. Eades, Mr. W. Randall, Mr. and Mrs. G. Holbrow, the Misses Holbrow, Private Edgar Holbrow, R.M.L.I., and Mr. H. Brewer. Mr. E. Jones (foreman) represented the firm of Messrs. R. Fussell (Ltd.), by whom Private Sheppard was formerly employed. Two of his old chums in the North Somerset Yeomanry, to which Private Sheppard was formerly attached, attended the service – Troopers Jack Hayward and Don Hand. The latter has lost a leg in his country’s service. Others present were ex-Private E. J. Tupper (Somerset L.I.), Mrs. F. Tipper, and Mr. and Mrs. J. Hunt. Old schoolmates who attended were Messrs. Podger, Webb, Sartain, Stagg, and Private Peaty (late of the Devon Regiment). The brass band of the A.S.C., “K” Company, R.S.P. Depot, attended, and headed the procession to the cemetery, playing Chopin’s “Marche Funebre.” The bearers and firing party were supplied by the Somerset Volunteer Regiment. The latter were commanded by R.S.M. Sinclair, and after the committal Trumpeter A. F. Cox, S.V.R., sounded the “Past Post.” [sic] The senders of wreaths included the relatives and friends, and Private Sheppard’s neighbours in Weston.

Captain Hugh Henry Lean, MC, Highland Light Infantry

Captain Hugh Henry Lean, MC, Highland Light Infantry (Staff Bde. Major 153rd Inf. Bde.)

Killed in action, 29 Jul 1917, aged 29

Poperinghe New Military Cemetery (II. G. 35), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of Maj.-Gen. K. E. Lean, C.B., and Mrs. Lean (nee Quin). Four times previously wounded in the War

Born: Dagshai, Punjab, 22 July 1888; Baptised 10 September 1888, son of Kenneth Edward Lean (Captain, Royal Scots Fusiliers) and Georgina Emily Lean (N-1-205, Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bengal, British India Office Births & Baptisms, The British Library; via Findmypast)

1911 Census: Outram Barracks, Dilkusha, Lucknow, India; aged 22, Lieutenant, K Company, 1st Highland Light Infantry,

Also commemorated on the Lynton war memorial and a memorial plaque in St Mary’s Church, Lynton (Devon); the latter states that he was killed in action near St Julien, near Ypres.

Private Reginald Charles Bourne, 6th Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 1 September 1917, p 2; via British Newspaper Archive.

Private Reginald Charles Bourne, 6th Bn., Northamptonshire Regiment; Service No. 40891

Killed in action, 8 Aug 1917, aged 19

Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial (Panel 43 and 45), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of Joseph Bourne, of “Audley Cottage,” Audley Park Rd., Bath.

1911 Census: 23 Wellington Buildings, Upper Weston; Reginald Charles Bourne, aged 12, at school; son of Joseph Bourne (gardener) and Alice Kate Bourne; one of eight children then resident.

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born Bath, enlisted Worthing

Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Graham Johnson, Royal Field Artillery

Bath Chronicle, 11 September 1915, p 3; via British Newspaper Archive.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Graham Johnson

33rd Div. Ammunition Col., Royal Field Artillery

Killed in action, 17 Sep 1917, aged 55

Reninghelst New Military Cemetery (IV. F. 8.), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Husband of Mary G. Johnson, of 2, The Grove, Weston Park, Bath

The name is spelled “Johnston” on both Weston memorials

1911 Census: Graham A. Johnson; 2, The Grove, Weston Park; aged 48; retired army officer; married to Mary G. Johnson

De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour, p 156 (via Findmypast):

JOHNSON, ARTHUR GRAHAM, Lieut.-Col., Royal Field Artillery, eldest s. of the late John Johnson, of Tunbridge Wells, M.D., by his wife, Ellen Jane Wright (The Limes, Derby); b. Tunbridge Wells, 30 Sept. 1862; educ. by the Rev. R. Fowler, of Tunbridge Wells, and at the Rev. Gascoigne’s School, Spondon, co. Derby; passed into the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, 2 March, 1880; was gazetted Feb. 1882; promoted Capt. 12 April, 1892, and Major 15 Oct, 1900; served 13 years in India, and retired 5 Nov. 1902. On the outbreak of war volunteered for service; rejoined 3 Sept. 1914; was promoted Lieut.-Col. 29 Jan. 1915; served with the Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders, in command of 33rd Divisional Artillery Ammunition Column; took part in the operations on the Somme, and was killed in action near Zonnebeke 17 Sept. 1917. Buried in Reninghelst New Military Cemetery, south-west of Ypres. His Chaplain wrote: “May I add quite humbly my own tribute to the memory of Col. Johnson. We have had many a talk on his favourite topics, and I have always been filled, like everyone else, with admiration at the iron and steadfast manner with which he soldiered. Few young men to-day could weather the storms of campaigning as he uncomplainingly did. He taught us lessons of utter devotion to duty, not least in his last great sacrifice, and grit, such as we are not likely to forget.” Brigadier-General Stewart, commanding the 33rd Divisional Artillery, wrote: “I regret most deeply to have to inform you that your husband, Lieut.-Col. Johnson, commanding the 33rd Divisional Artillery Ammunition Column, was hit this morning while in the forward area on duty. I deeply regret to say he was killed. Your husband died a gallant officer and gentleman, doing his duty in connection with his work, and one of his officers, Capt. [Henry] Rhodes, was killed beside him. The 33rd Divisional Artillery mourn with you for a comrade they admired and loved. I soldiered with him many years ago, and knew him well. May we all tender you our deepest sympathy.” General Blain also wrote: “I have just heard the sad news of your husband’s death in France. Although I left the command of the 33rd Divisional Artillery in April, I feel I must send you a line to say how much I sympathize with you, and how very distressed I am. Your husband was a very old friend of min since the days of Meerut in 1891. He will be a great loss to the 33rd Division; he was so zealous and never spared himself. The service has lost a very gallant and devoted officer,” said his Adjutant; “You will have heard ere this of the sad loss. I write to tender you the sincerest sympathy and condolence of the officers, N.C.O.’s and men of the Divisional Artillery Column. They one and all feel it a personal loss, and, as far as myself, I have lost a friend, as well as a kind and considerate commanding officer, having lived with him practically night and day for nearly two years. I do and shall miss him more that I can say.” Col. Henley-Kirkwood wrote: “It was with deep regret that I read in last evening’s paper a notice of the death – killed at the front – of your husband, and I desire to express on my own behalf, as well as on behalf of the Executive Committee of the National Service League, our most sincere sympathy with you. I am sure that not only all the members of the Committee, but also all the members of the league who had the privilege of knowing your husband, will join with me in deeply regretting the loss of such a keen and good soldier, and that he ended his career of great exertions in various public interests by giving his life for his country, will, when time somewhat softens the blow, be a source of true consolation to you.” He was a keen public worker in the cause of Tariff Reform and National Service, being honorary secretary of the Tariff Reform League, Bath, for some years. He m. at Dinapore, India, 15 Feb. 1894, Mary Gem, dau. Of Lieut.-Col. Spencer Cargill, Royal Artillery (retired), and had a dau., Elsie Cargill, b. 7 Dec. 1901 [at Ipswich].

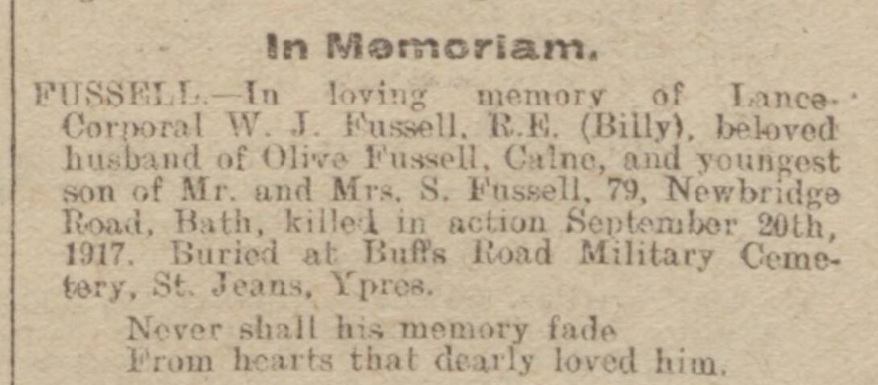

Lance Corporal William John Fussell, Royal Engineers

Bath Chronicle, 13 October 1917, p. 19; via British Newspaper Archive.

Lance Corporal William John Fussell, 503rd Field Coy., Royal Engineers; Service No. 504468

Killed in action, 20 Sep 1917, aged 26

Buffs Road Cemetery (E. 22), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of Samuel and Elizabeth Fussell, of Newbridge Rd., Bath; husband of Olive Edith Fussell, of 5, Pippen Rd., Calne, Wilts.

Bath Chronicle, 20 September 1919, p. 5; via British Newspaper Archive.

Born: William John Fussell, Bath, 2nd Q 1892

1901 Census: 21 Prospect Place, Weston; John W. Fussell, aged 9

1911 Census: 79 Newbridge Road, Bath; William Fussell, aged 19, electrical engineer; son of Samuel Fussell (carpenter and joiner) and Elizabeth Fussell

Married Olive E. Drew, Bath 1st quarter, 1916

Name only features on the memorial in the Church of All Saints; also commemorated on the war memorial at Calne

Lance Corporal Arthur Sidney Pickett, Royal Engineers

Bath Chronicle, 3 November 1917, p. 8; via British Newspaper Archive.

Lance Corporal Arthur Sidney Pickett, 146th Army Troops Coy., Royal Engineers; Service No. 35959

Killed in action, 24 Oct 1917, aged 29

Voormezeele Enclosures No. 1 and No. 2 (I. L. 31.), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of George and Emma Pickett, of 26, Church Rd., Weston, Bath; husband of Margaret R. Pickett, of 31, White Hill, Bradford-on-Avon

1911 Census: 26 Church Road, Upper Weston; Arthur Pickett, aged 22, carpenter; son of George Pickett (gardener in private family) and Emma Pickett; the youngest of four children then resident

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 3 November 1917, p. 8:

LOST BOTH THEIR SONS.

Mr. and Mrs. George Pickett, of 26, Church Road, Upper Weston, will receive much sympathy in the double bereavement they have suffered owing to the war – both their sons have now been lost. On Tuesday morning brought to Mrs. Pickett, of 84, High Street, Weston (formerly 3, Westbrook Villas), a letter containing the sad news that her husband, Lance-Corpl. Arthur Sydney Pickett, was killed on the 24th October. The communication was from Capt. J. H. Becker, R.E. who explained that a German shell burst quite close to a party of his company, killing Lance-Corpl. Pickett and a comrade. He states that the deceased soldier was one of the best of N.C.O.’s and was a great favourite with everyone, both officers and men. Lance-Corpl. Pickett, who was 29 years old, joined the regular Royal Engineers in May, 1915, and was trained at Chatham. He had been in France a considerable time, and when killed had returned to duty but a few days, as he had been away ill, in a hospital and convalescent home in France for two months. He leaves a widow and two children, the younger under nine months’ old. He was a carpenter in civilian life, having been apprenticed to the late Tom Crews, of Julian Rd., Bath, and remaining in the employment of that builder’s successor, Mr. Bright, till he enlisted. On April 15th last, his only brother, Pte. Frank Pickett, of the Devons, was drowned in the Mediterranean, the transport in which he was proceeding to Egypt having been torpedoed by enemy submarine. He was 36 years of age, and had been married quite recently. This elder son joined at Weston-super-Mare, where he was gardener to Prebendary Norton-Thompson, at the Rectory.

One of two brothers named on the memorial

Private Alfred Richard John Anstey, 2nd Battalion, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Bath Chronicle, 17 November 1917, p. 8; via British Newspaper Archive.

Private Alfred Richard John Anstey, 2nd R.M. Bn., R.N. Div., Royal Marine Light Infantry; Service No. PO/1987(S)

Killed in action, 26 Oct 1917, aged 19

Tyne Cot Memorial (Panel 1), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of Alfred and Sarah Anstey, of 65, High St., Upper Weston, Bath

Born 3rd quarter, 1898

1911 Census: 65 High Street, Upper Weston, Bath; aged 12, son of Alfred Anstey (domestic gardener) and Sarah Anstey; eldest of five children then resident.

ADM 159/206/1987, Admiralty: Royal Marines: Registers of Service, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

Alfred Richard John Anstey

Born 13 July 1898

Trade: Bookbinders apprentice

Religion: Church of England

Enlisted: Taunton (Bath), 17 Feb 1917, aged 18

At Deal (depot) Feb to Apr 1917; then HMS Victory V; joined 2nd R.M. Battn, 18 July 1917

Next of kin: Alfred Anstey (father), 65 High Street, Weston, Bath

Name on Weston memorial cross: “Pte. F. Anstey,” presumably for “Fred”

Enlisted in the Royal Marine Light Infantry at the same time as Private Edward James Holbrow (see entry below), and both were killed in action on the same day.

Private Edward James Holbrow, 2nd Battalion, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Private Edward James Holbrow, 2nd R.M. Bn., R.N. Div., Royal Marine Light Infantry; Service No. PO/1986(S)

Killed in action, 26 Oct 1917, aged 19

Tyne Cot Memorial (Panel 1), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of James and Ada Bertha Holbrow, of 69, High St., Upper Weston, Bath

James Edwin Holbrow, Born Bath (district), 3rd Quarter, 1898

1911 Census: 69 High Street, Upper Weston, Bath; Edward Holbrow, aged 13; son of James Holbrow (gardener) and Ada Holbrow; one of three children then resident

ADM 159/206/1987, Admiralty: Royal Marines: Registers of Service, The National Archives; via Findmypast:

Edward James Holbrow

Born 17 July 1896

Trade: Gardener

Religion: Church of England

Enlisted: Taunton, 17 Feb 1917, aged 18

At Deal (depot) Feb to Apr 1917; joined 2nd R.M. Battn, 18 July 1917 (assumed dead)

Next of kin: James Holbrow (father), 69 High Street, Weston, Bath

The 26th October 1917 was the opening day of the Second Battle of Passchendale, the phase of the Third Battle of Ypres that saw the Canadian Corps take on the final attempts to capture the village of Passchendaele.

The 2nd Battalion, Royal Marine Light Infantry were part of 188th Brigade in the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division. Together with the 58th (2/1st London) Division, the 63rd were part of XVIII Corps (Fifth Army), operating just to the north of the Canadians. The XVIII Corps sector during the Second Battle of Passchendaele was grim. North of the Bellevue spur, rain and artillery fire had conspired to convert the drainage systems of the Lekkerboterbeek and Paddebeek into a barely-passable swamp. Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson note that both XVIII Corps divisions were based in what were effectively swamps and that units in the front line had suffered shelling by gas and high explosive very shortly before the attack [7].

Then at zero hour 58 and 63 Divisions advanced into a series of machine gun nests. The terrain was so bad that many of the leading waves sank up to their shoulders. Rifles and Lewis guns became clogged and the barrage was lost. Only a derisory amount of ground was gained for a cost of 2,000 casualties.

The War Diary of the 2nd RMLI (WO 95/3110/2) does not contain that much detail:

Irish Farm. 25-10-17. Operation Order No 91 issued. Battalion proceeded into line p.m., and took up position for attack.

Front line. 26-10-17. 5.40 am. Battalion attacked enemy’s position opposite its front, in conjunction with other battalions of the 188th Infy. Bde. Objectives gained & consolidated. Casualties. 7 officers and 301 O.R’s.

27-10-17. Battalion consolidating position gained, relieved p.m. by Hawke Bn. & proceeeded to Irish Farm.

Irish Farm was to the north of the city of Ypres. On the 26th October 1917, the 188th Brigade were attacking to the north of the Canadian Corps, in the area around Varlet Farm and Banff House.

1918

Ten men from the village died in 1918, all but three of them while serving on the Western Front. Five of the nine died during various stages of the German Spring Offensive, Corporal George Edward Bond on the opening day of Operation Michael. Another two were killed in action during the Allied Advance to Victory, both probably around the French village of Epehy, near Cambrai. Privates Ernest and Walter James Lewis both died of illness at Chepstow after the Armistice, presumably the result of the influenza pandemic. Both had previously served overseas.

Corporal George Edward Bond, 8th Battalion, Rifle Brigade

Bath Chronicle, 16 December 1916, p. 11; via British Newspaper Archive.

Corporal George Edward Bond, 8th Bn., Rifle Brigade; Service No. S/26146

Killed in action, 21 Mar 1918

Pozieres Memorial (Panel 81 to 84), Somme

Soldiers Died in the Great War: residence: Bath; enlisted: Northampton

Born: Bath, 3rd Q, 1888

1891 Census: Locksbrook Terrace, Brass Mill Lane, Weston; aged 2

1901 Census: 5 River Terrace, Weston; Aged 13, errand boy

1911 Census: 17 Church Road, Upper Weston, Bath; aged 22, printer

Married: Winifred Mary Mapstone, All Saints, Weston, July 1915

One of three brothers named on the memorial

Second Lieutenant Stanley Reginald Butler, 7th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry

Second Lieutenant Stanley Reginald Butler, 7th Bn., Somerset Light Infantry

Killed in action, 27 Mar 1918

Pozieres Memorial (Panel 25 and 26), Somme

Born: 3rd Quarter, 1895, Bath, Somerset

1901 Census: 26 Primrose Hill, Weston, Bath; aged 5; the son of Walter Butler (a gardener) and Catherine Butler

1911 Census: 11 Primrose Hill, Weston, Bath; aged 15, office boy; the brother of Alice Etterley (head of household)

Private Harry Charles Stanley Higgins, 13th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 26 October 1918, p. 19; via British Newspaper Archive.

Private Harry Charles Stanley Higgins, 13th Bn., Gloucestershire Regiment (Forest of Dean Pioneers); Service No. 15042

Died, 29 Mar 1918, aged 26

Pozieres Memorial (Panel 40 and 41.), Somme

CWGC additional information: Son of Fredrick and Mary A. Higgins, of 6, Trafalgar Rd., Upper Weston, Bath

Somerset Baptism Index (Somerset Archives): Harry Charles Stanley Higgins, baptised Weston, 28 Feb 1892; residence: Gibbs Place; parents: Fredrick William Higgins (a coachman) and Mary Ann Higgins.

1891 Census: Gibbs Place, High Street, Weston, Bath; Frederick Higgins (aged 28, coachman, born Forest Hill, Kent) and Mary Higgins (aged 24, born Westbury); one child: Herbert (aged 3), Frederick’s widowed mother, Hester Higgins (aged 54, nurse), and Mary’s brother, Herbert Gunstone (aged 21, boot maker)

1901 Census: 15, High Street, Weston, Bath; Charles Higgins, aged 9; living with mother, Mary Higgins (aged 34); three brothers: Herbert (aged 13, telegraph messenger), Frederick (aged 4), Ernest (aged 2)

1911 Census: 15 High Street, Upper Weston, Bath; Charles Higgins, aged 19, book binding apprentice; parents: Fredrick Higgins (aged 48, coachman domestic, born Kent) and Mary Higgins (aged 44, born Dilton, Westbury, Wilts); two younger brothers: Fredrick (aged 14, shop assistant) and Ernest (aged 12, at school)

Private William Owen Hobbs, 19th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

Private William Owen Hobbs, 19th Bn., Lancashire Fusiliers; Service No. 46214

Killed in action, 25 Apr 1918, aged 36

Tyne Cot Memorial (Panel 54 to 60), West-Vlaanderen

CWGC additional information: Son of Mrs. Hobbs, of 124, High St., Upper Weston, Bath, and the late John Hobbs; husband of Ethel C. Hobbs, of 18, Prospect Place, Upper Weston, Bath

1911 Census: 124 High Street, Upper Weston, Bath; aged 28, house painter; son of William John (light haulier, born Calne) and Martha Hobbs (born Sherston)

Soldiers Died in the Great War: Formerly Royal Engineers (Service No. 183246)

Private Albert George Hawkins, 14th Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 8 June 1918, p. 19; via British Newspaper Archive.

Private Albert George Hawkins, 14th Bn., Worcestershire Regiment; Service No. 43823

Killed in action, 19 May 1918, aged 18

Englebelmer Communal Cemetery Extension (C. 14.), Somme, France

CWGC additional information: Son of Albert and Elizabeth Hawkins, of 4, Lansdown Place, Upper Weston, Bath

1911 Census: 4, Lansdown Place, Weston, Bath; Albert Hawkins, aged 10; son of Albert George Hawkins (aged 44, fireman) and Elizabeth Hawkins (aged 48, laundry work); one of eight children then resident

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born Batheaston; residence Bath; enlisted Bristol

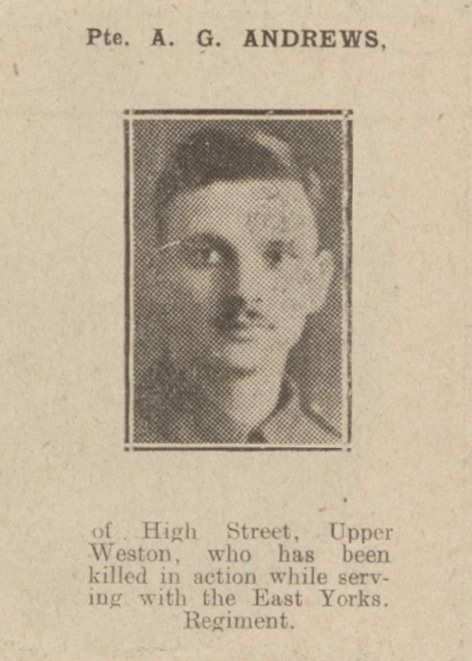

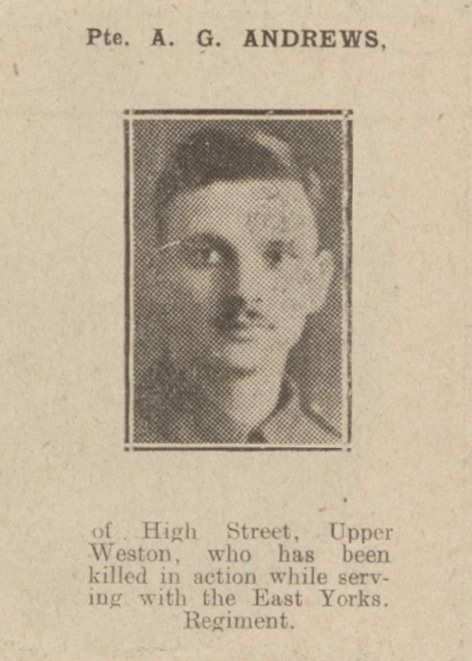

Private Alfred George Andrews, 7th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 21 September 1918, p. 15; via British Newspaper Archive.

Pte Alfred George Andrews, 7th Bn., East Yorkshire Regiment; Service No. 29247

Killed in action, 27 Aug 1918, aged 27

A.I.F. Burial Ground, Flers (III. K. 4.), Somme

Concentrated from Grass Lane Cemetery (one cross for eight burials), Trench Map ref. 57c.N.23.b.9.5. 57c.M.30.

Somerset Baptism Index: Baptised 19 Jan 1892, Twerton; parents: Isaac Andrews (Maltster) and Agnes Lavinia Andrews, 4 Charlton Bdge, Twerton

1911 Census: 6 Avon Buildings, Twerton, Bath; Alfred Andrews, aged 19, bread bakehouse assistant; son of Isaac Andrews (malthouse labourer, born Marshfield) and Agnes Lavinia Andrews; the eldest of five children then resident.

Bath Chronicle, 14 September 1918, p. 5:

UPPER WESTON SOLDIER KILLED.

News has just been received of the death in action of Private A. G. Andrews of the East Yorks Regiment, whose bereaved family reside at 66, High Street, Upper Weston. He joined the Army in December, 1914, and went to France a fortnight later as a baker in the A.S.C. Twelve months ago he was transferred to the East Yorks Regiment, and fell on August 27th. Private Andrews, who is the son-in-law of Mr. E. Taylor, 26, Green Park, was 27 years of age, and formerly worked at the Red House Bakery. He leaves a widow and two children.

Soldiers Died in the Great War: born Twerton; enlisted Bath; previously 3/3/029763 ASC

Second Lieutenant Ernest Frederick Bond, 5th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 16 December 1916, p. 11; via British Newspaper Archive.

Second Lieutenant Ernest Frederick Bond, attached 5th Bn., Royal Berkshire Regiment

Killed in action, 26 Sep 1918

Epehy Wood Farm Cemetery, Epehy (II. I. 4.), France (Nord?)

ADM 188/1044/13040, British Royal Navy Seamen 1899-1924; The National Archives; via Findmypast:

Born Bath, 22 Dec 1896

Occupation: Clerk

Joined RN 28 Apr 1915, discharged 8 Nov 1917 from RNAS, in order to be admitted to an Officer Cadet Unit (for Commission in Army)

1901 Census: 5 River Terrace, Weston, Bath; aged 4; son of Thomas Bond (gardener domestic) and Priscilla Bond

1911 Census: 17 Church Road, Upper Weston, Bath; aged 14, office boy; son of Priscilla Margaret and Thomas William Bond

One of three brothers named on the memorial

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 12 October 1918, p. 16:

THREE SONS KILLED

WESTON MOTHER’S CUP OF SORROW.

The greatest sympathy will be felt for Mrs. P. Bond, of No. 2, Moravian Cottages, Weston Road, Bath, who learnt on Monday that her youngest son, Second Lieut. Ernest Frederick Bond, Royal Berkshire Regiment, was killed in action on Sept. 26th. He is the third son to have laid down his life, and in the short space of three years Mrs. Bond has lost her husband and all her sons with the exception of the eldest. Second Lieut. E. F. Bond was educated at the Upper Weston School, and afterwards took employment in Bath and Trowbridge as a clerk. Soon after the outbreak of war he joined the R.N.A.S. as a writer. He was given his commission and went out to France with the Berkshire Regiment about two months ago. The news of his death was conveyed to his mother in a letter from his chaplain, which says that while in action with his company Second Lieut. Bond was struck by an enemy hand grenade. The deceased officer was only 21 years of age. Mrs. Bond’s surviving son, Lieut. T. G. Bond is at present on active service. For acts of gallantry he has been awarded the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre.

Bath Chronicle, 25 November 1916, p. 14; via British Newspaper Archive.

As the newspaper reports say, Ernest Frederick was the youngest of three Bond brothers that died during the war. Their older brother, Thomas Joseph H. Bond, survived the war, winning several medals. On the 25th November 1916 (p14), the Bath Chronicle reported on the award of a Military Cross to Company Sergeant Major Thomas Joseph Bond of the 1st Battalion, Royal Fusiliers:

WESTON MAN WINS MILITARY CROSS

News has been received by Mrs. T. W. Bond of Moravian Cottage, Weston Road, Bath, that her son, Company-Sergt.-Major T. J. H. Bond, now serving with the Royal Fusiliers, has been awarded the Military Cross for distinguished service in the field. Previous to this he had been twice mentioned in despatches for conspicuous gallantry on the Somme.

Company-Sergt.-Major Bond has been on active service since August, 1914, when he went to France, attached to the 3rd King’s Own Hussars, with the original British Expeditonary Force, and has taken part in many of the most important engagements, these including the retreat from Mons, the battles of the Marne, the Aisne and Neuve Chapelle. He is now on the Somme.

He is one of four brothers on active service, three of whom are in France, and the other in the Royal Navy.

The second son, Rifleman G. E. Bond, is in the King’s Royal Rifles; the third son, Lance-Corporal W. J. Bond, is in the Royal Engineers; and the fourth son, Writer E. F. Bond, R.N., is with the Royal Naval Air Service.

Company-Sergt.-Major Bond is an old scholar of Weston (Church of England) Boy’s School, and is the first of the school to be decorated with the Military Cross. Before the war he was employed by Mrs. Carr, of Weston Manor.

On three separate occasions during the present campaign Company-Sergt.-Major Bond had received an official card, signed by the Major-General commanding his division, for distinguished conduct in the field.

CSM Bond’s first Military Cross citation was published in the Supplement to the London Gazette of the 8th December 1916, p. 12109:

16776 C.S.Maj. Thomas Joseph Bond, R. Fus.

For conspicuous gallantry in action. He assumed command of and led his company with great courage and initiative. Later, with a few men, he repulsed an enemy counter-attack.

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 30 November 1918, p. 11:

Mrs. P. Bond, of Moravian Cottages, Weston Road, has had four sons serving in the war. Three of them have made the supreme sacrifice, as already mentioned in these columns. The wife of the only surviving son, 2nd Lieut. T. J. Bond, 1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers, has just heard that her husband has been awarded a bar to the Military Cross bestowed upon him in November of last year. This gallant young officer has served right through the war, and has seemed to bear a charmed life, for though he has been in many a hot corner and has been gassed, buried by shell bursts on several occasions, and has suffered from trench feet, he has never been wounded. In addition to the Military Cross with bar, he holds the Mons Star and the Croix de Guerre.

Thomas Joseph Bond:

Born Bath, 2nd Quarter,1886

Baptised Weston, 30 May 1886

1911 Census: Roberts Heights, Pretoria, Transvaal, South Africa; a Private in the 3rd King’s Own Hussars

After the war, enlisted in the Royal Tank Corps, 7 Feb 1922, Bath, aged 35 (Service No. 397119); husband of Mrs E. Bond, 23 Rivers Street, Bath; discharged Canterbury, 6 Feb 1924

Private Alfred Lewis, 2nd Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment

Private Alfred Lewis, 2nd Bn., Worcestershire Regiment; Service No. 57666

Killed in action, 29 Sep 1918, aged 19

Pigeon Ravine Cemetery, Epehy (I. C. 16.), France

CWGC additional information: Son of Mr. F. W. Lewis, of 9, Manor Rd., Weston, Bath

1891 Census: Manor Road, Weston, Bath; Frederick M. Lewis, aged 26, gas stoker; Jane E. Lewis, 26; children: Henry C., Amy E., Frederick M.

1901 Census: 9, Manor Road, Weston, Bath; Alfred Lewis, aged 2; son of Frederick Lewis (aged 36, gas works stoker) and Jane Lewis (aged 36); children: Amy, Frederick, Agnes, Ernest, Walter, Alfred

1911 Census: 9 Manor Road Weston Bath; Alfred Lewis, aged 12; son of Frederick Lewis (aged 46, stoker, widower); one of six children then resident: Amy (aged 22), Frederick (aged 20, smith), Louie (aged 18, dress maker), Ernest (aged 16, farm boy), Jenny (aged 9)

One of four brothers named on the memorial

Private William George Kite, 1st Garrison Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

Bath Chronicle, 14 December 1918, p. 19; via British Newspaper Archive.

Private William George Kite, 1st (Garr.) Bn., Devonshire Regiment; Service No. 43552

Died, 24 Nov 1918, aged 31

Jerusalem War Cemetery (Q. 138.), Israel/Palestine

CWGC additional information: Husband of Mabel Kite, of 5, Mill Lane, West Twerton, Bath.

Bath Chronicle, 14 December 1918: notes that he died of malaria

Marriage: William G. Kite, married Mabel Hampton, Bath (district), 1st Quarter, 1914

Probably: Mabel Hampton, born Bath (probably Twerton), 2nd Quarter, 1885

1891 Census: Rivers Place, Twerton, aged 6, scholar, daughter of Joseph and Sophia Hampton

1901 Census: 17, River Place, aged 16, laundress

1911 Census: 5 Mill Lane, Twerton, aged 26, packer in laundry

Trooper Ernest Lewis, North Somerset Yeomanry

Private Ernest Lewis, North Somerset Yeomanry; Service No. 165882

Died: 24 Dec 1918, aged 23

Chepstow Cemetery (H.), UK

CWGC additional information: Son of Mr. F. W. Lewis, of 9, Manor Rd., Weston, Bath

Born: Bath,1st Q, 1895

Died: Chepstow, 4th Q, 1918, aged 23

One of four brothers named on the memorial

Driver Walter James Lewis, Royal Engineers

Driver Walter James Lewis; Service No. 52408

56th Div., Signal Coy., Royal Engineers

Died 25 Dec 1918, aged 22

Chepstow Cemetery (H.), UK

CWGC additional information: Son of Mr. F. W. Lewis, of 9, Manor Rd., Weston, Bath

Born: 1st Quarter, 1897, Bath

Died: Chepstow, 4th Q, 1896, aged 22

WO 363 – First World War Service Records ‘Burnt Documents’:

Walter James Lewis

Enlisted: Bath, 15 Sep 1913, aged 19

Occupation: footman

Admitted Military Hospital Chepstow 13 Dec 1918 suffering from influenza, died there from Influenzal Bronchitis whilst on leave from BEF

Served overseas: Sep 1915-Aug 1917 (323 days), Jan – Dec 1918 (334 days)

Medical notes also indicate service in Salonica and Malta (1917), Invalided to England (malaria) 5 Sep 1917

Pension sent to Miss A. L. Lewis (sister), 9 Manor Road

Brother: F. Lewis, age 29, 68 St Mary Street, Chepstow

One of four brothers named on the memorial

Frederick William Lewis (father), born Bath, 2nd Quarter, 1865

Jane Elizabeth King (mother), born Bath, 4th Quarter, 1864; 1871 Census: daughter of Charles and Rhoda King, Wellington Buildings, Weston

Marriage: Frederick William Lewis married Jane Elizabeth King, Twerton, Bath, 2nd Quarter, 1887.

Jane Elizabeth Lewis died Bath, 3rd Q, 1905, aged 40

1939 Register: Lewis, Frederick W., b. 23 Mar 1864, gas worker retired; Lewis, Agnes L., b. 17 Oct 1892

Frederick William Lewis, 9 Manor Road, Upper Weston, died Bathavon (district), 27 Jan 1951, aged 85.

Currently unidentified

There were two names on the Weston memorials that I was unable to match with anyone in the CWGC database.

Private H. Frankham

There were several possibilities, but no definitive way to identify Private H. Frankham.

One of the possibilities was Private G. H. Frankham, who definitely had a connection with Upper Weston. On the 1st December 1917, the Bath Chronicle published a photograph of Pte. Frankham stating that he lived at 114 High Street, Upper Weston. He was with the 9th Devonshire Regiment (who for most of the war were with 20th Infantry Brigade in the 7th Division). It may be possible to link this person with the George Henry Frankham of 20 Church Street, Upper Weston who joined the 4th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry in 1899, when aged 17 (and then discharged in 1903). The name of “G. H. Frankham” is also listed in the Roll of Honour inscribed on the war shrine in All Saints Church, Corston, but is not in the list of those who had died from that parish. More information would need to come to light before any connection with the Weston war memorial could be proved.

Bath Chronicle, 1 December 1917, p. 2; via British Newspaper Archive.

Another possibility is suggested by a family that lived at Weston and Twerton:

1891 Census: Westhall Gardens, Weston Bath; William and Harriett Frankham, and four children

1901 Census: 17 Percy Terrace, Twerton, Bath; William Frankham and five children boarding at the household of Harriett Chorley, a charwoman that had been born at Newport (Monmouthshire).

1911 Census: 6 Longmead St, Twerton, Bath; William Henry Frankham (aged 69, stone mason labourer, born Weston, Somerset), married to Harriett Frankham (aged 54, born Bath); children listed at: Kate (aged 21, laundress), Henry (aged 19, iron foundry labourer), Gladys (aged 16), Herbert (aged 13, at school), Reginald (Aged 9, at school).

William H. Frankham died in the 2nd Quarter of 1912, aged 70.

Both Henry and Herbert Frankham would have been at an appropriate age to have served during the war, but Harriett, Henry and Herbert Frankham were all recorded by the Electoral Registers for 1920 and 1921 as resident at 1, Gladstone Terrace, Twerton. Service records survive for Herbert Henry Frankham, who served with the Devonshire Regiment (Service No. 53081) and the Labour Corps during the war, enlisting in 1917 (WO 363, First World War Service Records ‘Burnt Documents’).

As none of these identifications are particularly satisfactory, Private H. Frankham and his exact link with Weston will have to remain a mystery for the time being.

Private T. Marshall

Private T. Marshall was similarly difficult to track down. One possibility might be:

Thomas Marshall, born Bath (district). 1st Quarter, 1896

1911 Census: No 1, Montrose Cottages, Upper Weston, Bath; Thomas Marshall (aged 15, errand boy messenger, born Bath); son of Frederick Charles Marshall (aged 49, gardener, born Wells) and Sarah Ann Marshall (aged 47, born Malmesbury); one of three sons then resident.

Thomas Marshall, died Bath (district), 4th Quarter, 1917, aged 21

I have searched the Bath Chronicle (via the British Newspaper Archive) and the genealogical databases in Findmypast for some evidence of this Thomas Marshall having served in the armed forces during the war, but with no success.*

[* For an identification of Thomas Marshall, please see the update below]

References:

[1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission: https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/

[2] Findmypast (£): https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

[3] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette; via British Newspaper Archive (£): https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

[4] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 August 1919, p. 19; via British Newspaper Archive.

[5] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1 June 1918, p. 8; via British Newspaper Archive.

[6] A war record of the 21st London Regiment (First Surrey Rifles), 1914-1919 (ca. 1928; Naval & Military Press reprint), p. 251.

[7] Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Passchendaele: the untold story, 3rd ed. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), pp. 174-175.

Update August 11th, 2023 — Private Thomas Marshall:

Through the pension claims records available from Ancestry, I have been able to find out a little bit more about Pte. T. Marshall. He served as Private 70434 Thomas Marshall of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

Thomas Marshall attested at London on the 20th October 1915, joining the RAMC Depot at Aldershot. He was later posted to E Coy. (28 October 1915) and then X Coy. (28 April 1916). On the 8 July 1916, however, Pte Marshall was discharged, as being “no longer physically fit for war service” (British Army World War I Pension Records 1914-1920; via Ancestry – source: WO 364, Soldiers’ Documents from Pension Claims, First World War, The National Archives, Kew).

The papers contain a medical report that was made at the Military Hospital at Codford (Wiltshire) on the 23 June 1916. The case history includes the following:

About ten months ago he “caught a cold,” since when he has had cough and expectoration. He continued his duties until the 12 June 1916 when he reported sick with severe pain in left chest. On the 17th June 1916 he was admitted to Codford Military Hospital for the same trouble. He has sickness & vomiting at times.

The diagnosis was: “Invasion of tubercle bacilla” [or bacilli], not caused “by active service, climate, or ordinary military service” (to use the terminology of the pro forma).

The medical summary in Marshall’s discharge papers concluded that the cause of Pte Marshall’s discharge was that he was: “Medically unfit, Tubercle of Lung,” adding that the cause was: “Not the result of, but aggravated by ordinary military duty; disability permanent.” The records also include a completed Pension Form 36 noting that Marshall died on the 11 December 1917.

Because his death was not deemed to have been the result of “ordinary military service” or duty, it seems that Pte. Marshall did not qualify for a war grave. He was buried in Locksbrook Cemetery in Bath.

Thomas Marshall had been born at Bath (registration district) in 1896, the son of Frederick Charles and (Sarah) Ann Marshall, who were living at Montrose Cottage. Thomas was baptised in April 1896, and admitted at All Saints, Weston on the 31 May the same year (this may mean that he was baptised at home, perhaps due to illness). At the time of the 1911 Census, the fifteen-year-old Thomas was living with his family at No. 1, Montrose Cottages, the middle one of thee sons. His father (aged 49) was working as a domestic gardener, as was his older brother, Joseph Horace Richmond Marshall (23). At the time, Thomas himself was working as an errand boy for a nurseryman. Joseph Horace Richmond Marshall died at Bridgend (registration district ) in 1919, aged 31.