“To-day I found in Mametz Wood

A certain cure for lust of blood.”

From: Robert Graves, “A Dead Boche.” in: Fairies and Fusiliers (London: William Heinemann, 1917), p. 33 [1].

; Muirhead Bone, Ruined Trenches in Mametz Wood, from: The Western Front, drawings by Muirhead Bone, Pt. III (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, & Co., 1917), no. VII. Source: HathiTrust Digital Library, via Yale University: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ yale.39002013479150

Last month I was intrigued by something included in one of Paul Reed’s excellent The Old Front Line podcasts [2]. At the end of his June 6th episode on “Walking the Somme: Mametz Wood,” Paul talked about a wartime photograph of Mametz Wood mounted on card, one of a collection that he had discovered in a junk shop in Littlehampton [3]. The photographs were of places the Welsh Division had fought during the First World War and had been taken by an officer of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Paul didn’t know that much about the photograph, except that the equipment used must have have been a proper, full-frame camera, and that the back of the card read: “Mametz Wood, before the attack,” with the name of D. J. Davies of Lampeter (who he knew had produced postcards). A copy of the photograph formed part of the gallery of images accompanying the podcast, and had been previously published in Reed’s book on Walking the Somme [4].

While I knew that I would be unlikely to shed any light on the origins of this specific photograph, I did wonder how easy it might be to find information on a Lampeter-based photographer named D. J. Davies. I was a student in Lampeter in the 1980s, and assumed that a town of its size would probably not have been overloaded with professional photographers in the first decades of the twentieth century. My initial thought was to look in Welsh Newspapers, a collection of digitised newspapers made freely available by the National Library of Wales [5]. The collection includes newspapers in both Welsh and English published up until 1919, so I thought that there would be a good chance that Mr Davies might be mentioned somewhere there.

Sure enough, the newspapers contained several mentions of a D. J. Davies, photographer (or D. J. Davies, Studio), of College Street, Lampeter. The newspaper reports indicated that Mr Davies had been responsible for giving occasional lantern presentations to various Lampeter societies before the war. These meetings seem to have mostly been held at Capel Soar, a large Congregational chapel. The following selected extracts show that the topics of the talks varied quite widely (and did not always involve lantern slides):

The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 5 March 1909 [6]:

CHRISTIAN ENDEAVOUR SOCIETY. — On Friday evening last Mr. D. J. Davies, photographer, of this town, gave an interesting entertainment to the members of this Society, at Soar, by means of the lantern. He had obtained from the London Missionary Society about 60 slides depicting Oriental customs and habits, and these he exhibited on the screen.

Welsh Gazette and West Wales Advertiser, 10th March 1910 [7]:

“Central Africa” — At the weekly meeting of the Soar C.E.S. on Friday evening, the Rev. E. Evans presiding, Mr. D. J. Davies, College-street, gave an illustrated lecture on “Central Africa.”

The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 11th March 1910 [8]:

Soar Chapel. — A meeting of the Christian Endeavour Society was held on Friday with the Rev G. Evans in the chair. Mr D. J. Davies, photographer, gave illustrations by means of the lantern of the work of the Lwamba Mission in north-east Rhodesia under the London Missionary Society. Mr E. D. Rees explained the pictures as they were thrown on the screen.

The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 28th February 1913 [9]:

CHRISTIAN ENDEAVOUR SOCIETY. — At the weekly meeting of this society at Soar on Friday evening last, Mr. John Evans, of Bettws Bledrws School, read an interesting and exhaustive paper on Welsh customs and manners.” Mr. D. J. Davies. photographer. College-street, presided, and an interesting discussion followed.

The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 20 March 1914 [10]:

The Institute. On Friday evening an interesting lecture was delivered at the Institute by Capt. B. Davies-Evans, Peterwell, on “Salmon and Eels and their Ways.” The lecture was illustrated by lantern views, the lantern being manipulated by Mr. D. J. Davies, photographer, and was listened to with rapt attention. The president, Mr. A. R T. Jones, J.P., occupied the chair.

The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 20th March 1914 [11]:

LECTURE. — The first of a series of lectures, arranged by the Men’s Institute Literary Committee, was given on Friday evening, when Mr. B. Davies-Evans, Peterwell, delivered an interesting lecture on “Salmon. Eels, and their habits.” The lecture, illustrated by lantern views, under the manipulation of Mr. D. J. Davies, Studio, was thoroughly enjoyed by the large number present. At the close Mr. Davies-Evans answered several questions submitted by local anglers, and showed salmon scales by means of a microscope and lens. On the proposition of Mr. A G. Harries, seconded by Mr. A. R. T. Jones, a hearty vote of thanks was passed to, and acknowledged by the lecturer. We hope to have the pleasure of listening to another lecture on “Natural History” by Mr. Davies-Evans, who is an acknowledged expert on the subject.

The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 20th November 1914 [12]:

Recruiting Meetlng. — On Thursday evening of last week, Mr. H. Lancaster (late provincial, secretary of the Primrose League), delivered an address at Victoria Hall on ”Why we Went to War.” The lecture was illustrated by means of lantern slides shown by Mr. D. J. Davies, photographer. In the course of a few remarks, Alderman Walter Davies, who presided, said it was the first occasion he had appeared in public in the role of mayor. He promised to do all he could to further recruiting in the town and also to alleviate distress caused by the war. Songs were sung by Miss Annie Hughes, Miss M. J. Jones, and Miss May Richards, Mr Ivor C. Jones accompanying on the piano. A vote of thanks to the speaker was passed on the proposition of Principal Bebb [of St David’s College], seconded by Professor A. W. Scott. A vote of thanks to the artistes was accorded on the proposition of Dr. Walker, seconded by Councillor D. F. Lloyd. A similar compliment was paid to the Chairman, and the meeting concluded with the singing of the National Anthem.

The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 11th December 1914 [13]:

SOAR. — The weekly meeting of the Mutual Improvement Society was held on Friday evening, when an instructive paper was read by Mr. Evan Price on “The Chacteristics [sic] of the Age.” Mr. D. J. Davies. photographer, occupied the chair. The following also spoke, viz.: — Messrs. J. C. Davies, Tom Davies. J. T. James. J. T. Richards. D. M. Davies, Timothy Richards, E. D. Rees and Mrs. Rees, Bee Hive.

Perhaps the most interesting mention of D. J. Davies, photographer, discovered in Welsh Newspapers, however, was a reference in the Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser of the 4th July 1919 to a talk given by a Captain E. Evans, M.C. at the vestry room at Shiloh (a Welsh Calvinist Methodist chapel), a talk that included an exhibition of lantern slides [14]:

LAMPETER.

[…]

On Wednesday, June 25th, the congregation at Shiloh was entertained at the vestry room by Mr. Matthews, of Ffosyffin, near Lampeter. The tea was followed by an exhibition of lantern slides kindly given by Capt. E. Evans, M.C. They illustrated various scenes and episodes in the Great War on the French front, such as trenches, dug-outs, shelled cathedrals, ruined villages and homesteads. &c. The pictures were explained in an interesting manner by Capt. Evans himself, and the lantern was excellently manipulated by Mr. D. J. Davies. photographer, Lampeter, one of the captain’s orderlies in France. Votes of thanks were proposed by the chairman (the Rev. W. Llewelyn Davies) and seconded by the Rev. Oswald Williams, B.A., after which the National Anthem was sung.

One is left wondering whether that photograph of Mametz Wood may have featured in that lantern presentation!

The report from the Shiloh meeting also provided a few more things to follow up. Firstly, it showed that D. J. Davies had served in the Army in some capacity during the war. Secondly, with a little bit of digging around, it was possible to match Captain E. Evans, MC with the Medical Officer of the 11th Battalion, South Wales Borderers, who had been awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Mametz Wood [15].

A quick search of the genealogical records on Findmypast [16] showed that some of the service records of 11/22590 Lance Corporal David Jones Davies of Lampeter were available in the WO 363 ‘Burnt Documents’ series [17]. The surviving records mostly relate to Lance Corporal Davies’s medical and discharge records, but they still provided insight into his military career.

Service history:

David Jones Davies enlisted, aged thirty-eight, at Llandudno on the 7th January 1915, at first joining the 15th (Service) Battalion (1st London Welsh), Royal Welsh Fusiliers (Service No. 22729). He afterwards transferred to the 11th (Service) Battalion (2nd Gwent), South Wales Borderers (Service No. 11/22590).

Private Davies seems to have first served with ‘A’ Company of the 11th South Wales Borderers (SWB), which became part of 115th Brigade in the 38th (Welsh) Division. He embarked for France at Southampton on the 3rd December 1915. However, from the 26th April 1916, Davies seemed to suffer from a long series of illnesses. His “Casualty Form – Active Service” (Army Form B. 103) is full of information about various admissions to field ambulances and hospitals. For example, he was admitted to 130 Field Ambulance twice in April and May 1916 suffering from influenza, then twice again to 11th CRS in May. He seems to have survived the 38th Division’s brief, but intense, spell on the Somme at Mametz Wood in July 1916, but was granted leave from the 22nd September to the 1st October 1916. He was then promoted Lance Corporal on the October 1916.

Lance Corporal Davies was admitted to No. 10 Stationary Hospital at St Omer on the 27th January 1917. The detail on the Casualty Form is illegible, but other documents in the service records relating to demobilisation and pension entitlements suggest that he may have been suffering from exposure (the winter of 1916/17 was an exceptionally cold one). At the end of February 1917, he was admitted to 131 Field Ambulance, once again suffering from influenza.

Davies returned to duty in March 1917, but seemed to be then mainly based at divisional headquarters, dealing with baths and laundry. In May 1917 he was admitted again to 131 Field Ambulance, with a not yet diagnosed (NYD) condition, then in June to 129 Field Ambulance with debility. He re-joined divisional HQ in July 1917 and seems to have remained there until he was once again granted leave from the 21st December 1917 to the 4th January 1918. On the 6th February 1918, Lance Corporal Davies was posted to the 10th SWB, presumably because the 11th SWB were to be disbanded as part of the divisional reorganisations of February 1918.

In early 1919, Lance Corporal Davies was transferred to England (Chisledon) for demobilization, reverting to the rank of Private. He was demobilised on the 13th March 1919, formally being transferred to Class “Z” of the Army Reserve.

David Jones Davies was aged forty-two at the time of his discharge. His service records contain additional paperwork from a Medical Board conducted after his discharge, which seems to have related to pension entitlements. The completed forms assert that Davies had suffered repeated attacks of “trench fever” since April 1916, and that this had affected his health — “man complains of palpitations and breathlessness on exertion since having trench fever in France.” After medical examinations, the board accepted Davies’s claims, which were attributed to active service, although the board concluded that the illness was “now in a very quiescent state.”

These documents are important because they confirm the statement in the Shiloh meeting report that David Jones Davies had served for a time as a doctor’s orderly, as well as his role in divisional baths and laundry.

Personal and family life:

With access to some of Lance Corporal Davies’s service records, it was possible to fill in some other details of his life from the other genealogical records available from Findmypast.

David Jones Davies was born at Lampeter on the 1st January 1877, the son of Benjamin and Elizabeth Davies. He was baptised at Lampeter on the 29th April 1877, where the register records his father’s occupation as a coal and timber merchant [18]. While there was far more than one Benjamin Davies in late-nineteenth-century Lampeter, correlation with the entry in the baptismal register and with census records suggests that he was the Benjamin Davies (a merchant) that married Elizabeth Jones at Llanifihangel Ystrad (Ystrad Aeron) on the 9th October 1872 [19].

David Jones Davies featured in the 1881 Census, when the family were living at Harford Square, Lampeter. At that time, Benjamin Davies was thirty-seven years old and working as a manager of a coal merchants, while his wife Elizabeth was thirty-two. David Jones Davies was five-years-old and still at school. He had an older sister, Mary Ann, who was aged eight, and a younger brother, John Christmas (spelled “Xmas” in the census return), who was aged four. The household also had a servant, Ann Davies, an eighteen-year-old general domestic, who had been born at nearby Cellan.

At the time of the 1891 Census, the family were living at 23, Bridge Street, Lampeter. Benjamin Davies seems to have been elsewhere, but his wife Elizabeth was aged forty-one. There were four children: Mary Anne (aged 17, a pupil-teacher), Thomas (15, a college attendant), David (14, like Mary Ann, a pupil-teacher), and John Christmas (13, a printer’s apprentice). The occupation “pupil-teacher” seems to refer to an apprentice system for teachers.

By the time of the 1901 Census, David Jones and John Christmas Davies were living at 46, Bridge Street, the household of their older sister, Mary Anne Davies. It’s difficult to disambiguate without additional information, but their mother may have been the Elizabeth Davies that died at Lampeter in 1893, aged 43. In 1901, Mary Ann Davies was twenty-seven, and working as an assistant teacher at a board school. John Christmas Davies was twenty-three and working as a printer’s compositor. David Jones Davies himself was twenty-four years old and working as a solicitor’s clerk (Lance Corporal Davies’s service records stated that his previous employer had been Winter & Bothamley, (i.e. Messrs Winter, Bothamley, and Co.), solicitors, of 16 Bedford Row, London, W.C.).

Things had changed yet again by the time of the 1911 Census. David Jones Davies was thirty-four years old and working as a photographer. He was still part of the household of his older sister, who was now living at Talsarn House, College Street, Lampeter. Since the 1901 Census, Mary Anne had been both married and widowed, so she was now Mary Anne Evans, aged thirty-seven, a fancy goods dealer. She also had two young children: Elizabeth Myfanwy (aged six) and Margaret Dorothy (aged 4). Also living at Talsarn House was Mary Anne and David Jones’s father, Benjamin Davies, a sixty-seven-year-old farm labourer. The 1911 Census also records Mary Ann and David’s younger brother, John Christmas Davies, living at 37, Bridge Street, part of the household of his widowed father-in-law, John Jones.

The death of Mary Anne Evans’s husband was extremely tragic. Mary Anne Davies had married Thomas Evans at Lampeter on the 4th December 1901. He died around five years afterwards, as reported on in the Welsh Gazette and West Wales Advertiser of the 27th December 1906 [20]:

TRADESMAN’S TRAGIC END. A painful sensation was caused in the town on Wednesday afternoon week, when it became known that Mr. Thomas Evans, butcher, College-street, had been found dead in a stable loft at the back of his house. Deceased, who was only 31 years of age, opened business at Lampeter some six or seven years ago. He was a son of Mr. Evan Evans, Red Lion, Talsarn, and leaves a widow and two children. An inquest touching the death was conducted by Dr. Abel Evans, district coroner, on Thursday afternoon, before a jury consisting of the following: — Messrs. Walter Davies (foreman), T. J. Megicks, Corner Shop; Richard John, borough surveyor; E. D. Rees, station-terrace; Rees Davies, saddler; Tom Jones, draper; D. Emlyn Davies, tailor; John Jones, College-street; William Davies, saddler; William Janes, Bryn road; J. S. Parry; and Evan Evans, cabinet maker.

Mrs. Mary Ann Evans, the widow, said she last saw her husband alive about 12 noon on the previous day, the 19th inst. She knew he was in trouble about money matters, and he was very despondent. A gentleman from Aberystwyth called to see him on Wednesday morning, and she sent a servant man to look for him at Davies, the saddler. He returned, and said he could not find his master. Then she sent her brother to Dulas Hall to look for him, and then she saw people rushing to the yard at the back.

Rhys Hughes, draper, said his premises were next door to those of the deceased. Between 12.30 and 1 o’clock on Wednesday, George Gittens, in the deceased’s employ, asked him if he had seen his master. He said no. Gittens then said. “The door of the hay loft above the stable is fast, and I cannot get in there. I am afraid he is inside.” They both tried the door again, hut failed to open it; it being fastened on the inside. He went down into the stable, and found a hatchet there, with which he broke three bars from the hayrack, and through the opening climbed into the loft. There he found the deceased hanging from a beam by a rope round his neck. Having opened the door for the servant man to enter, they both cut him down. Artificial respiration was tried, but without success. He had had a conversation with the deceased about his affairs om Wednesday morning. He was very despondent, but expressed no intention of doing away with himself.

George Gittens, said his master told him about nine oclock [sic] on Wednesday morning to return a beast to Parkneuadd, Llanfair-Clydogau. When he came back he was told by Mrs. Evans to look for his master. He went, but failed to find him. Then he went to the stable loft to get a feed for the pony, but failed to get in as the door was fastened on the inside. They then broke into the loft as described by Mr. Hughes, and there found the deceased.

A verdict of “Suicide whilst temporarily insane’ was returned. The jury returned their fees to the widow.

The funeral took place on Saturday, and was largely-attended, the interment taking place at the Parish Churchyard. Deep sympathy is felt with Mrs. Evans and her family.

It seems that after the end of the war, David Jones Davies returned to his photography business in Lampeter. Internet searches for “D. J. Davies Lampeter” retrieve many images of postcards that he produced, which include many topographical views of Wales [21]. His photographs were also occasionally published in newspapers like the Western Mail and in books.

The 1939 Register (available via Findmypast) records that David J. Davies, photographer, was still living at Talsarn House in College Street, with his niece Elizabeth M. Evans, who was by that point a head teacher.

David Jones Davies died in 1947, aged 70, and was buried at Lampeter on the 31st January 1947.

Captain Evan Evans, MC, Royal Army Medical Corps:

We have already noted that the Captain Evans that gave the talk at Shiloh in 1919 had formerly been Medical Officer of the 11th SWB. This was Captain Evan Evans, MC of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Dr Evans also had a very strong connection with Lampeter.

Evan Evans is a fairly common name in Wales, which made researching Dr Evans’s life and background quite challenging. However, using clues from the Welsh Newspapers archive, it was possible to track his general progress through the census and other records (again using Findmypast).

Evan Evans was born at Llanwenog (some records state Aberaeron) on the 10th August 1874, the son of Captain John Evans and Anne Evans. By the time of the 1881 Census, the family were living at 5 Cadwgan Place, Aberaeron (the building was also known as Milford House; it is now Listed Grade II, and featured in 1970 on a postage stamp, part of a set of commemoratives on rural architecture). In 1881, the household included: John Evans (aged 37), a merchant, and his wife Anne Evans (30). Evan D. Evans (aged 6) was the eldest of three children, followed by John G. (5), and David G. (3). Also part of the household was Thomas Davies (23), a clerk, and Hannah Thomas (16), a general servant.

The family were still resident at Cadwgan Place, Henfynyw (Aberaeron) at the time of the following census in 1891. The occupation of John Evans, the head of household, was specified in the census return as a corn merchant. Evan, John, and David had been joined by Thomas G. (aged 8). There were also two general servants and a domestic servant: Daniel Jones (23), Arthur J. Driver (19), and Anne Jones (22).

John and Anne Evans were still living at 5, Cadwgan Place at the time of the 1901 Census. John (57) had extended his role to be a grain and timber merchant. Of their children, Evan and John were living elsewhere, leaving David (aged 23) with his eight-year-old brother, Jenkin A. There were also four servants, all of whom seem to have been part of John Evans’s business: Evan Jones (aged 21, a commercial clerk), John Evans (20, a corn miller), Evan Davies (16, a warehouseman), and David E. Owens (15, a carter).

That same census recorded the twenty-six-year-old Evan Evans lodging at 19, Water Lane, Lambeth (London), a resident medical officer. He was living back in Cardiganshire by the time of the 1911 Census, lodging at 11, College Street, Lampeter, now a thirty-six-year-old medical practitioner. The census return also noted that he was capable of speaking both Welsh and English.

Evan Evans and three of his brothers served in the Army during the First World War. A glowing tribute to the family (complete with photographs) appeared in the Cambrian News of the 9th November 1917 [22]:

Distinguished Aberayron Family.

Captain Evan Evans, M.C., M.D.; Major David Evans; Lieutenant Albert Evans, M.C.; sitting, Mr. John Evans, F.C.I., public analyst of Sheffield, York, and Cardiganshire; inset, Capt. Garfield Evans, M.D. These are the five sons of Captain and Mrs. Evans, Milford House, Aberayron. Four are in the army. Two have won the M.C. in France. Dr. E. Evans was medical practitioner at Lampeter; Major David Evans before the war was county valuer for Cardiganshire and Pembrokeshire; Mr. John Evans is public analyst for Sheffield and Cardiganshire; Captain Garfield Evans, M.D., before the war had commenced practice at Port Talbot. He is attached to the Welsh Hospital and is now in India. Mr. Albert Evans was medical student at Guy’s when he joined the colours. The record is an extraordinary one for more than one reason.

Captain Evan Evans was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Mametz Wood, when (as we have noted) he was Medical Officer of the 11th SWB,. The public announcement in the Edinburgh Gazette of the 1st January 1917 included his name in a long list of award recipients with no citations [23]. However, a footnote in Atkinson’s history of the South Wales Borderers, notes that Captain Evans was awarded the MC for “his gallantry and devotion to duty in this action [Mametz Wood]; he did splendid work and ran repeated risks in getting to the wounded and succouring them” [24]. The War Diary of the 11th SWB also recorded the award (and a few others) on the 6th January 1917 [25]:

Battalion Orders for this day contained the following announcement:

The Commanding Officer has great pleasure in announcing the following and hearty congratulates the recipients.

London Gazette, January 2nd 1916 [sic]

Capt Evan Evans, RAMC, attd. 11th SWB – Military Cross, for gallantly attending to wounded under continuous heavy fire at Mametz Wood July 7th 16

11/21561 Sgt Edwards A Coy 11th SWB – Distinguished Conduct Medal

Capt C. E. Browning B Coy 11th SWB – Mentioned in Despatches

Atkinson’s footnote also provided a list of persons serving in the 10th and 11th SWB that had been “brought to notice by the Brigadier for good work.” For the 11th Battalion, the names include a Private D. J. Davies, although, without service numbers, it is not possible to ascertain whether this person might have been the David Jones Davies that has been the main subject of this post.

After Mametz Wood, Captain Evans continued to be attached to the 11th SWB. The Cambrian News of the 26th January 1917 noted that he had recently been visiting Lampeter on leave [26]:

LAMPETER.

PERSONAL. — Dr. Evan Evans, M.B.B.S., is home on leave. He looks well and was heartily congratulated by his many friends upon his winning the military cross.

The MBBS is a reference to Dr Evans’s medical qualifications: Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery.

Captain Evans was wounded later that year. On the 31st July 1917, the 38th Division were involved the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, the opening offensive of the 3rd Battle of Ypres. Captain Evans’s name appears in a long list of casualties noted in the War Diary of the 11th SWB [27]. The Cambrian News of the 10th August 1917 reported his wounding in a long list of Lampeter casualties [28]:

LAMPETER.

[…]

A big list of casualties at the front has been received in this district during the present week. Pte. W. J. Davies, Welsh Guards, of Aberdauddwr Farm, near Lampeter, has been killed. He was formerly a policeman at Burry Port. Among those wounded are Surgeon-Captain Evan Evans, M.C., but it is understood that his wounds are not serious; Lieut. J. T. James, Compton House, who was caught by a German bomb when leading a raiding party; Lieut. D. Jones, Coedmorfach; Corpl. Tom Lewis, Bwlchffin, Cwmanne, who had been previously wounded at Loos; Corpl. Tom Morgan Davies, Wesley House, Barley Mow: and Pte. Wentworth Megicks, The Laurels, Bridge-street. Sapper Alfred Davies. College-street, has been gassed.

After the end of the war, Dr Evans returned to his medical practice in Lampeter, eventually becoming medical officer for the borough and a Justice of the Peace. At least once he attended a reunion dinner of the 11th SWB [29]:

GWENT S.W.B. REUNION

The sixth annual reunion dinner of the 11th Battalion South Wales Borderers (2nd Gwents) was held at Newport on Saturday. Capt. J. Richards (Swansea) presided, and guests of honour included Capt. H. M. Salmon (Cardiff City Battalion), Capt. W. S. Edwards (Newport), Capt. J. E. Mills (Llanidloes), Dr. Evan Evans (Lampeter), and Capt. W. T. Harris.

It seems that he never married. The 1939 Register records him living at Mayfield, Lampeter with a housekeeper, Rachel Mathews. After the Second World War, he was awarded the freedom of the borough of Lampeter [30]:

LAMPETER’S TWO NEW FREEMEN

LAMPETER on Thursday conferred the freedom of the borough on Councillor William Lewis, J.P., and Dr. Evan Evans, J.P., medical officer for the borough. There was a large gathering at the Town-hall, presided over by the Mayor (Alderman O. Saunders Davies).

[…]

HONOURING EX-SERVICE MEN

The Rev. T. Oswald Williams proposed the admission of Dr. Evan Evans and spoke of his good work as medical practitioner at Lampeter for 40 years and said he had held the post of medical officer of health with distinction. He was president of the local branch of the British Legion, and through him they would be honouring the ex-Service men. Mr. W. R. Bowen seconded.

In 1956, Dr Evans was 82 years old and described in the Western Mail as the “oldest [medical] practitioner in Cardiganshire” [31].

The 38th (Welsh) Division at Mametz Wood:

The 10th and 11th South Wales Borderers (SWB) were both New Army units formed by the Welsh National Executive Committee after the outbreak of the war [32]. The 10th (Service) Battalion (1st Gwent) was formed first, at Brecon in October 1914, the 11th (Service) Battalion (2nd Gwent) following on the 5th December. For most of the duration of the war, the 10th and 11th SWB formed part of 115th Brigade in the 38th (Welsh) Division [33]. From the time of the Division’s arrival in France up until the divisional reorganisations of February 1918, the other infantry units in the 115th Brigade were the 16th Battalion (Cardiff City), Welsh Regiment and the 17th Battalion (2nd North Wales), Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

The 38th Division had arrived in France in early December 1915. By the end of the year, the 10th SWB had moved to trenches in the Laventie sector, attached to the Guards Division for instruction in trench warfare. At the same time, the 11th SWB were based in trenches around Richebourg. The battalions would stay in French Flanders for many months, alternating between billets and front-line trenches — e.g. at Pont du Hem (La Gorgue), Neuve-Chapelle, Festubert, Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée, and Fauquissart — with occasional spells spent training.

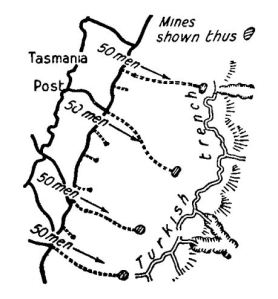

In mid-June, the 10th and 11th SWB moved to the divisional training area around Tincques, where the 38th Division was assembling and conducting manoeuvres. From the 26th June, they and the rest of 115th Brigade started moving towards the Somme front, via Gézaincourt, Toutencourt, Acheux-en-Amiénois, and Buire-sur-l’Ancre. During this time, the “Big Push” on the Somme had got underway. On the 5th July, the 10th and 11th SWB marched to bivouacs near Mametz and Carnoy. There, the 38th Division would join Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne’s XV Corps, relieving the 7th Division in trenches to the south of Mametz Wood [34].

On the 1st July 1916, the British XV Corps (7th and 21st Divisions) had managed to capture Mametz village, and had spent the following few days pushing forward, and consolidating just short of Mametz Wood. The plan for the following stage of the offensive was for the 38th Division to assault the wood from the south, while the 17th (Northern) Division would attack towards Quadrangle Support Trench further north. The pause in operations enabled the German defenders to turn Mametz Wood into a formidable obstacle. Facing the 38th was a long, thin extension of the wood shaped like a hammer, and known as the Hammerhead.

Contalmaison, Mametz Wood, Bazentin-le-Petit. and Montauban. Detail from: Map of the Somme area; Scale: 1:40,000; Edition: 2; Published: December 1916: https://maps.nls.uk/view/101723165

Bad weather caused some delays, but the 38th Division attack finally went in at 8.30 am on the 7th July 1916. The 115th Brigade had been chosen to lead the attack, with the 11th SWB on the left and the 16th Welsh Regiment on the right. The 10th SWB was in reserve in Montauban Valley. The attack was a complete failure.

The 11th SWB War Diary (WO 95/2562/2) tends to be succinct to the point of terseness. For example, the entry for the 7th July 1916 reads in its entirety [35]:

[Carnoy]. 7. Attacked Mametz Wood at 8.42 AM in conjunction with Cardiff (City 16th Welsh), attack failed. Battalions reformed and made a second attack at about 11 AM, this attack also failed. Casualties: killed, Lt Hamer actg adjt; wounded, Capt Monteith, Capt Browning, 2nd Lt Lowe, 2nd Lt Woodcock, 2nd Lt Whittaker, 2nd Lt. Salathiel, 2nd Lt Carrington, 2nd Lt Ackerley and 120 O.R.

The 10th SWB were in reserve for the 7th July attack, and their War Diary (WO 95/2562/1) is, if anything, even less informative [36]:

MAMETZ, Sht AMIENS 17 [a map reference]. 6.7.16. Battalion at Bivouac &afterwards marched to trenches as reserves to 16th Welch Regt & 11th S.W.B.’s attack on MAMETZ WOOD.

TRENCHES. 7.7.16. Battalion in Trenches in reserve to 16th Welch Regt & 11th S.W.B.’s attack on MAMETZ Wood. Casualties: 1 Officer (Lt. Col. S. J. Wilkinson, D.S.O., commanding battn.) killed & 20 ORs wounded & 2 killed.

TRENCHES. 8.7.16. Battalion in Trenches till 1 AM & returned to Bivouac between MAMETZ & CARNOY.

In order to get a fuller picture of the failed 7th July attack, it is necessary, therefore, to consult other sources. The regimental history, C. T. Atkinson’s The History of the South Wales Borderers, 1914-1918, does helpfully contain a more detailed account [37]:

The attack had as its first objective a line just inside the Eastern edge of the wood. This secured, the attackers were to push on North and West and endeavour to reach a ride running North and South about midway across the wood. Starting at 8.30 a.m. the attack at once encountered a heavy fire from rifles and machine guns, while the German guns which had already replied vigorously to our bombardment redoubled their fire. The 11th [SWB] pushed forward well nevertheless, but before long machine guns from Bazentin-le-Grand Wood and from Sabot and Flatiron Copses caught them in flank, inflicting many casualties, and brought the attack to a standstill. On the right the leading men were within 200 yards of their objective, on the left they were nearly double that distance off. Satisfactory observation and registration had been impossible and in consequence the British bombardment had been neither sufficiently accurate or effective. A second attack was ordered for 11.15 a.m., but the half an hour’s fresh bombardment again proved inadequate. The machine guns were not subdued, and this advance also was soon held up.

By this time the 10th S.W.B. had received orders to support the attack and Colonel Wilkinson had come forward to reconnoitre. When the second advance failed, A and D Companies under Captain Galsworthy were ordered up to reinforce the firing line, followed an hour later by the remaining two under the C.O. Setting out from their bivouac near Mametz the 10th advanced across a maze of battered trenches, progress being much impeded by heavy rain and the consequent mud, and eventually arrived at the point of deployment just before 3 p.m. At 3.15 p.m. A, B and D also attacked, but with no better success than before. The machine guns were still in action and their fire made progress virtually impossible. Colonel Wilkinson was killed in bringing forward the second wave and the advance soon faded away.

Divisional Headquarters were keen for another assault to take place on the 7th and had planned another supporting barrage, but the commander of 115th Brigade, Brigadier-General Horatio James Evans, eventually cancelled the attack. The account of this episode in Llewellyn Wyn Griffith’s Up to Mametz provides a good example of the vagaries of battlefield communication at this stage of the war [38].

As the war diary extracts suggest, the 11th SWB in particular suffered many casualties. Some of those reported wounded in the War Diary would later die of wounds [39]. For example, Second Lieutenant Ewart Gladstone Salathiel of the 11th died on the 17th July, being buried at Rogerstone. His family placed a notice in Y Goleuad on the 28th July 1916, noting that he had been a teacher at the Council School at Cwmffrwdoer, Pontypool [40]:

SALATHIEL. — Ar faes y frwydr, Lifftenant Ewart Salathiel, South Wales Borderers, Risca. Bu’n athraw yn Ysgol y Cyngor, Cwmffrwdoer, gei Pontypwl.

After the failed attack of the 7th July, the 115th Brigade returned to their bivouacs at Mametz and Carnoy, while other units in the 38th Division prepared the ground for another assault on the wood. The 10th and 11th SWB would start moving to new positions on the 9th July, in preparation for renewing the attack on the 10th July.

Things were also changing at a higher level. The commanding officer of the 38th Division, Major-General Ivor Philipps, was sacked on the 9th July and, on the advice of the Commander in Chief, temporarily replaced by Major-General Herbert Edward Watts, the commander of 7th Division. While Brigadier-General Evans had been restricted by XV Corps regarding the timing and size of 115th Brigade’s attack on the 7th July, General Watts was given a much freer hand and, for the attack on the 10th, he decided on a much heavier assault, to be led by four battalions [41].

The War Diary of the 11th SWB continued to use as few words as possible to describe progress on days subsequent to the 7th July attack [42]:

8. Relieved by 113rd Brigade at 3 AM.

9. Resting in Bivouac till 8 AM when D and C Co’s went up to Catterpillar [sic] Wood and Marlboro Wood and relieved the 10th Welsh 114 Bdge. A & B Co went to Mametz Wood to reinforce 113th Bdge.

10. C & D held Caterpillar and Marlboro Wood, and A & B attacked in Mametz Wood.

11. C & D still in the two woods and were relived by 8th Devons at 12 PM.

A & B were relieved in Mametz Wood by two Cos from the 7th Division.

Casualties: Capt Lewis and 2nd Lt Fletcher killed; 2nd Lt Travis, 2nd Lt Heppel, wounded; 2nd Lt Miller-Hallett missing.

Carnoy. July 12. Bivouac all day, resting.

The War Diary of the 10th SWB contained a fraction more detail, but not that much [43]:

MAMETZ, Bivoucac, Sht. AMIENS 17. 10/7/16 & 11/7/16. Battalion at Bivouac until 12. Noon when it departed for Trenches to take part in attack on MAMETZ Wood by 38th Division. Attack carried out, portion of wood captured. 3 Field Guns & 2 Heavy Guns taken by Bn & marked 10th S.W.B. Casualties: Killed: 2nd Lt M. J. Everton & 2nd Lt R. P. Taylor & 21 O Ranks; wounded: Major C. W. Harvey, Capt. Galsworthy, (both at Duty), Lieuts Gill & Parry R.B., 2nd Lts Davenport H.H., Davies, D.C.; missing total 6. D. 10/20189 Pte. Griffiths T., D., 10/03170 Pte Lavender J.A., B. 10/24172 Pte Bishop H., B. 10/21329 Evans D., B. 10/20526 Pte Hughes F., B. 10/20974 Pte Davies J. The Battalion suffered an intense bombardment during the night of 11-12 of July 1916.

MAMETZ WOOD, Sht AMIENS 17. 12/7/16. Battalion at MAMETZ WOOD & returned to Bivouac at 9 AM & stayed at Bivouac for the day.

“Attack carried out, portion of wood captured” was an extremely succinct description of the work undertaken in Mametz Wood during the attack of the 10th and 11th July 1916.

The Cambria Daily Leader of the 27th September 1916 managed to get a fuller account from a officer in one of the Welsh Regiment battalions involved in the attack [44]:

HOW MAMETZ WAS CAPTURED.

Work of a Welsh Regiment.

In an account of the gallant part played by the Welsh Regiment in the capture of Mametz Wood, one of the Battalion officers who is at present in Swansea remarked to a “Leader” reporter that it would be difficult to imagine a tougher proposition than the task set the lads.

The Battalion went into action on July 10th before dawn. They were occupying a position known as White Trench — an old German trench — where they had spent two nights. Their objective was a strip of the wood, 1,000 yards in length, deviating to the north, and the country in between was of a difficult character.

“Our advance,” the officer remarked, “was preceded by a heavy bombardment by our artillery from 3.30 to 4.15 a.m. We left the trench for the attack at five minutes past four, having 1,000 yards to go before reaching the wood. We had ten minutes to cover that distance. We had to go down a steep bank into the valley and then up again to the wood. The barrage was so beautifully timed that it only lifted five seconds before our company got in. We had advanced in eight waves, two platoons in each wave. We got into the wood and pushed right through our portion to the other end, a, distance of about a mile. As we advanced stage by stage to the cross-roads the barrage kept on lifting. We held the wood with comparatively small numbers, supported by other brigades on the right and left, until four o’clock the next, morning, when we were relieved. A battalion supported us very, well.”

Describing the ordeal the Battalions went through in the advance, our informant remarked that what with our own and the enemy’s barrage, the wood was a mass of artillery fire. Hand-to-hand fighting and bombing took place right throughout the wood. The wood was extraordinarily thick, the Germans had tied the branches of the trees together, and it was extremely difficult to force a passage through. Moreover, there were concealed machine-guns in the coppices on either side of the front of the wood.

For the attack of the 10th July, the 115th Brigade was initially held in reserve. Atkinson’s regimental history contains an account of how both the 10th and 11th SWB started to get drawn into the battle during the afternoon of the 10th July [45]:

Gradually the [initial] attacking brigades used up their reserves, and about midday the 10th S.W.B. were ordered forward. Moving off about 1 p.m. the 10th reached the Eastern edge of Mametz Wood without many casualties, despite the heavy shelling which greeted them. Here Major Harvey had just deployed his men when he received orders to postpone his attack in order to allow of a fresh bombardment. At 4 p.m. he was to clear the Eastern corner of the wood.

Attacking with great vigour and dash the 10th made excellent progress at first, taking several prisoners and driving the surviving defenders out into the open, where in bolting towards Sabot and Flatiron Copses they gave targets to the rifles and machine guns of the 11th S.W.B. holding Caterpillar and Marlborough Woods. But opposition became more serious as the advance progressed; much trouble was experienced with dealing with machine guns, bombers who tried to work along a trench on the edge of the wood met stubborn resistance and had many casualties, and the 10th were held up a little short of their objective, though two bombing attacks which Sergeant Edwards led with much courage and initiative gained not a little ground. Elsewhere the attack was less successful. Detachments fought their way forward despite savage opposition to within about three hundred yards of the Northern edge, but the portion of the wood West of the railway remained untaken. In the end an irregular line was formed, the 10th S.W.B. lining the Eastern edge S.W. of Flatiron Copse with their left thrown back at right angles towards the middle ride.

Before this the 115th Brigade had received orders to relieve the other brigades, now quite exhausted. Half of it was already in action in the wood and the two companies of the 11th S.W.B. could not be moved from Caterpillar and Marlborough Woods, but the relief was at length carried out and the other half-battalion of the 11th came in between the 10th and the central ride, with the 17th R.W.F. and 16th Welch beyond it. The night was disturbed by much firing and many alarms, but no real counter-attack. Shortly before dawn Major Harvey made a fresh effort to secure his objectives, attacking them simultaneously from both flanks. This was most successful and by 5 a.m. the disputed points were in the hands of the 10th, who captured several more prisoners and in clearing up the captured position took possession of several guns and howitzers; Sergeant J. H. Williams, who distinguished himself by his courage and skill, led his men with great dash and good work was done by many others. General Watts [the commander of 7th Division, temporarily in charge of the 38th] meanwhile had given orders for a fresh effort to clear the untaken portion. This eventually got going at 3.15 p.m., and earlier start having been delayed by a barrage which our guns put down. The R.W.F. and Welch met very stubborn resistance and could make little progress, but the 11th S.W.B. fared better and fought their way to the N.E. corner of the wood, despite heavy machine-gun fire and strong opposition, only to find their left completely “in the air.” This was about 5.30 p.m. and for some time Colonel Gaussen and his men managed to maintain their ground, though German reinforcements prevented them pushing West along the Northern edge. The Brigadier called on the other battalions to advance again and reduce the pressure on the 11th, but after gaining a little ground they were again driven back and about 9 p.m. the 11th had to fall back to a line about three hundred yards short of the Northern edge. Here they remained till early next morning (July 12th), when the Twenty-First Division took over the greater part of Mametz Wood, the Seventh coming in on their right and relieving the 11th S.W.B. in Caterpillar and Marlborough Woods.

Mametz Wood was the 38th Division’s first experience of a full-scale attack on the Western Front. Hard fighting in woodland in bad weather must have been a brutal introduction to the Battle of the Somme. After their relief, the 10th and 11th SWB were at first transferred to the northern part of the Somme front (around Hébuterne and Courcelles-au-Bois), before moving to the Yser front via Candas and Saint-Omer by the end of the month. The 38th Division would not return to the Somme that year.

Mametz Wood, however, was now in the hands of the British. That summer, other Allied units would fight their way through the woodland and copses of that part of the Somme front, working their way through Bernafay and Trônes Wood, Bazentin Ridge, Longueval and Delville Wood, with the eventual capture of High Wood (Bois des Fourcaux) during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on the 15th September 1916.

The War Diary extracts provide an indication of the overall casualties of the 10th and 11th SWB during the Mametz Wood operations in early July 1916. Atkinson commented that neither had, “all things considered, suffered very heavily” [46]. Despite that, the commanding officer of the 10th (Lieutenant-Colonel Sidney John Wilkinson) was killed [47], and two subalterns and 29 other ranks were killed or missing, with another nine officers and 140 other ranks wounded. The 11th SWB lost even more. Atkinson doesn’t provide exact numbers, but he records that around fourteen officers were killed or missing, with ten wounded, plus what must have amounted to around 200 other ranks killed, missing or wounded.

Muirhead Bone, Welsh Soldiers, from: The Western Front, drawings by Muirhead Bone, Pt. III (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, & Co., 1917), no. LVII. Source: HathiTrust Digital Library, via Yale University: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/yale.39002013479150

There is a memorial to the 38th Division inside the church at Mametz. In 1987, another memorial, one that incorporates a very striking sculpture of a red dragon, was placed in the valley facing Mametz Wood [48].

And here and there and huddled over, death-halsed to these, a Picton-five-feet-four paragon for the Line, from Newcastle Emlyn or Talgarth in Brycheiniog, lying disordered like discarded garments or crumpled chin to shin-bone like a Lambourne find.

From: David Jones, In parenthesis [49].

References:

[1] Robert Graves, “A Dead Boche.” in: Fairies and Fusiliers (London: William Heinemann, 1917), p. 33:

https://archive.org/details/fairiesfusiliers00gravuoft/page/32

[2] Paul Reed, The Old Front Line WW1 Podcast: https://oldfrontline.co.uk/

[3] Paul Reed, “Walking the Somme: Mametz Wood”:

https://oldfrontline.co.uk/2020/06/06/walking-the-somme-mametz-wood/

[4] Paul Reed, Walking the Somme: a walker’s guide to the 1916 Somme battlefields, 2nd ed. (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011), p. 177.

[5] Welsh Newspapers: https://newspapers.library.wales/home

[6] The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 5 March 1909, p. 8; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3763905/3763913/75/

[7] Welsh Gazette and West Wales Advertiser, 10th March 1910, p. 4; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3881242/3881246/31/

[8] The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 11th March 1910, p. 3; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3411723/3411726/34/

[9] The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 28th February 1913, p. 5; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3764857/3764862/49/

[10] The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 20 March 1914, p. 3; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3412212/3412215/22/

[11] The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 20th March 1914, p. 5; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3678127/3678132/54/

[12] The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 20th November 1914, p. 5; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3412563/3412568/46/

[13] The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 11th December 1914, p. 7; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3678462/3678469/73/

[14] The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser, 4 July 1919, p. 3; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers):

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3679429/3679432/44/

[15] C. T. Atkinson, The history of the South Wales Borderers, 1914-1918 (London: Medici Society, 1931), Naval and Military Press reprint, p. 247.

[16] Findmypast: https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

[17] WO 363, British Army WW1 Service Records, 1914-1920, ‘Burnt Documents,’ The National Archives; via Findmypast.

[18] Cardiganshire Baptisms, 1856-1891, Carmarthenshire Record Office, Welsh Archive Services; via Findmypast.

[19] Cardiganshire Marriages And Banns, 1837-1919, Welsh Archive Services; via Findmypast.

[20] Welsh Gazette and West Wales Advertiser, 27th December 1906, p. 4; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers):

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3866866/3866870/38/

[21] An example would be the view of Hafod published in: “Some puzzling pictures of Hafod,” Letter from Aberystwyth, 15 November 2017:

https://www.letterfromaberystwyth.co.uk/some-puzzling-pictures-of-hafod/

[22] The Cambrian News and Merioneth Standard, 9th November 1917, p. 3; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3413978/3413981

[23] The Edinburgh Gazette, Supplement, No. 13033, 1 January 1917, p. 33; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://www.thegazette.co.uk/Edinburgh/issue/13033/page/33

[24] Atkinson, op cit., p. 247.

[25] WO 95/2562/2, War Diary, 11th Battalion, South Wales Borderers, The National Archives, Kew.

[26] The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard, 26 January 1917, p 3; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3413609/3413617/100/

[27] WO 95/2562/2

[28] The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard, 10 August 1917, p. 5; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers): https://papuraunewydd.llyfrgell.cymru/view/3413861/3413866/62

[29] Western Mail, 21 November 1938, p. 8; via British Newspaper Archive.

[30] Western Mail, 26 April 1946, p. 3; via British Newspaper Archive.

[31] Western Mail , 17 August 1956, p. 4; via British Newspaper Archive.

[32] The Long, Long Trail: South Wales Borderers:

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/regiments-and-corps/the-british-infantry-regiments-of-1914-1918/south-wales-borderers/

[33] The Long, Long Trail: 38th (Welsh) Division:

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/order-of-battle-of-divisions/38th-welsh-division/

[34] Siegfried Sassoon describes the relief of the 1st Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers by units of the 38th Division in his Memoirs of an infantry officer (London: Faber and Faber, 1965), pp. 61-62: “Visualising that forlorn crowd of khaki figures under the twilight of the trees, I can believe that I saw then, for the first time, how blindly war destroys its victims.” Sassoon is sympathetic, but some of his comments, e.g., “I understood the doomed condition of these half trained civilians,” also seem a little condescending.

[35] WO 95/2562/2

[36] WO 95/2562/1, War Diary, 10th Battalion, South Wales Borderers, The National Archives, Kew.

[37] Atkinson, op. cit., pp. 242-244.

[38] Llewellyn Wyn Griffith, Up to Mametz (London: Faber and Faber, 1931); short extracts printed in John Richards (ed.), Wales on the Western Front (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1994), pp.78-91.

[39] Atkinson, op. cit., p. 244.

[40] Y Goleuad, 28 July 1916, p. 13; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers):

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3494491/3494504/42/

[41] Michael Renshaw, Mametz Wood, Battleground Europe (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 1999), pp. 77, 91.

[42] WO 95/2562/2

[43] WO 95/2562/1

[44] Cambria Daily Leader, 27 September 1916, p. 2; via the National Library of Wales (Welsh Newspapers):

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4102273/4102275/28/

[45] Atkinson, op. cit., pp. 245-246.

[46] Ibid., p. 247.

[47] Pam and Ken Linge, Missing but not forgotten: men of the Thiepval Memorial, Somme (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2015), p. 61.

[48] Wikipedia, Mametz Wood Memorial:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mametz_Wood_Memorial

[49] David Jones, In parenthesis (London: Faber and Faber, 1937), p. 182.

Further reading:

Steven John, Welsh at war: the grinding war: the Somme and Arras (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2018).

David Jones, In parenthesis: seinnyessit e gludyf ym penn mameu (London: Faber and Faber, 1937) — an amazing work, concluding with an account of the assault on Mametz Wood by someone who was there.

Michael Renshaw, Mametz Wood, Battleground Europe (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 1999) — an account that doesn’t forget the efforts of the 17th Division.

Update July 10th, 2023:

I thought that it would be worth trying to find David Jones Davies in the 1921 Census. The census return recorded that he was forty-four years old, a photographer working on his own account. He was living at Talsarn House, Lampeter, which was the household of his sister Mary Anne Evans (aged 46, an elementary school teacher, working for the Cardigan Educational Authority at Silian Church of England School). The household also included Mary Anne’s daughters – Elizabeth Myfanwy Evans (aged 16, a student elementary school teacher, also working for the Cardiganshire Educational Authority, but at the Council School at Gartheli) and Margaret Dorothy Evans (aged 14) – and her and David Jones Davies’s father (Benjamin Davies, aged 76, a retired coal merchant).